Journalists generally frown on question mark headlines. Ian Betteridge, a British technology journalist based in Canterbury, and director COVID-19 has caused me to write at least one and think about more question mark headlines over the last three years than ever before.

Journalists generally frown on question mark headlines. Ian Betteridge, a British technology journalist based in Canterbury, and director COVID-19 has caused me to write at least one and think about more question mark headlines over the last three years than ever before.

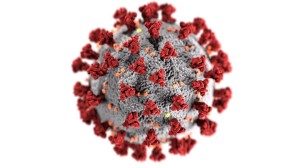

I started off on Jan. 23, 2020, writing, “The fire this time? Pandemic prose, and waiting and watching for the ‘big one’ (https://soundingsjohnbarker.wordpress.com/2020/01/23/the-fire-this-time-pandemic-prose-and-waiting-and-watching-for-the-big-one/). I penned those words on a cold winter January night. At that time, COVID-19 hadn’t been invented by the World Health Organization (WHO) as the official moniker for what was then simply known provisionally as Novel Coronavirus 2019-n, or CoV2019-nCoV, designating it as a novel coronavirus. When I first wrote about it, the WHO was still a week away from designating the newly-discovered coronavirus a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC). The WHO then waited another six weeks almost until March 11 to decide a global pandemic was under way.

Eight months after my first novel coronavirus post, I wrote: “… the question mark, of course, can be dropped. It is indeed the fire this time. Except when it is not. That is the paradox of COVID-19. The vast majority of people infected with COVID-19 will recover. The elderly and those of any age group with comorbidities are at greatest risk. Except there will be apparently otherwise healthy young people who die of COVID-19, too. Many, in fact, although nothing like their elders (https://soundingsjohnbarker.wordpress.com/2020/09/23/covid-19-the-fire-that-darkened-the-world/).

“People infected with the flu almost always get sick. They are rarely asymptomatic. Many people with COVID-19 are asymptomatic, pre-symptomatic, or only mildly symptomatic, but contagious in any of those three states, making them walking viral bombs.”

After more than three long years of the COVID-19 global pandemic, hope is on the breeze early this May. Two years ago today on May 9, 2021, Manitoba was going into its third lockdown and third coronavirus wave, reporting the third highest number of COVID-19 cases per capita in all of Canada and the United States. Tomorrow, most of the last remaining masking requirements for health-care facilities in Manitoba are set to be lifted, although the public health order changes will not apply in settings where care is being provided to particularly vulnerable populations, including cancer patients and transplant recipients. Masking requirements in these locations will be clearly indicated with signage and the requirement will apply to health-care workers, visitors and all patients “who are able to tolerate wearing a mask.”

While COVID-19 is still a global pandemic, it is no longer a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. After a five hour meeting in Geneva – its 15th regarding COVID-19 – the WHO’s International Health Regulations (2005) (IHR) Emergency Committee recommended on May 4 “that it is time to transition to long-term management of the COVID-19 pandemic” and advised “the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic … is now an established and ongoing health issue which no longer constitutes a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. WHO Director-General, Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesu, who has the final say, concurred with the committee.

“While we’re not in the crisis mode, we can’t let our guard down,” said Dr. Maria Van Kerkhove, WHO’s Covid-19 technical lead and head of its program on emerging diseases. She added that the disease and the coronavirus that causes it are “here to stay.”

On Thursday, the United States is set to end its own federal public health emergency declaration, which dates back to Jan. 31, 2020.

Some 675,000 Americans died over three years between January 1918 and December 1920 during the three waves of the Spanish Flu pandemic when the country’s population was 103.2 million. Today, the population of the United States is more than 332 million and more than 1.1 million Americans have died of COVID-19. The world population in 1918 was about 1.8 billion, compared to about 8 billion people today, and at least 50 million people died of the Spanish Flu. Almost 7 million have died of COVID-19.

Kent Sepkowitz, a physician and infectious disease expert at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, said yesterday “the slow and steady, data-based rollback of these previously necessary interventions surely is the right thing to do … as is assuring that masks and vaccines and test kits (though these soon will no longer be free to all) and the entire apparatus of pandemic control remain available for those who feel uneasy still.”

Sepkowitz says “the specifics of the next bad thing” is not “what keeps us infectious disease specialists up at night. Rather, it is the deepening uncertainty as to whether the U.S. will be able to respond to the next crisis. The loose collection of anti-vaxxers, anti-pharma, anti-science, pro-conspiracists has hardened into a movement.”

What that means, says Sepkowitz , is that “at the next public health crisis we will need to deal not only with a pathogen but also with a well-organized, non-reality-based community that seems tireless in its pursuit of alternative facts. Though the majority of people in the U.S. are vaccinated, seem to believe in science and simply want to go about their business, the noisy minority will likely make the Trump-organized Operation Warp Speed response to the Covid-19 pandemic seem like a once-in-a-lifetime moment of amity, a peaceful agreement across all ideologies and political stripes.”

Dr. Brent Roussin, Manitoba’s chief public health officer, on May 5 called on people to move forward following the World Health Organization’s declaration that the global COVID-19 emergency is over.

“That doesn’t mean that the pandemic is over … but I do think that we need to find ways to heal,” Roussin said. He told CBC that Manitoba used extraordinary measures to stem the tide of COVID-19 in the province, but they are not a normal way to deal with health issues.

“If you think about the pre-pandemic years, there’s always been people who have been vulnerable, susceptible, and more at risk than others. But we don’t deal with that in a restrictive manner,” he said.

Roussin said he’s optimistic that people will start to heal from societal divisions that arose during the pandemic.

“I’m quite hopeful, especially in Manitoba. We know what Manitobans are made of,” he said.

You can also follow me on Twitter at: https://twitter.com/jwbarker22