It is Christmas 1996. I am working as the managing editor of The Kingston Net-Times, during the pioneering days of Canadian online journalism. From day one, we published no print edition and our local stories in that groundbreaking digital newspaper were updated on the fly throughout the day, but there were few bells and whistles, as very, very few of our online readers had cable broadband internet in 1996. Who remembers dial-up?

It is Christmas 1996. I am working as the managing editor of The Kingston Net-Times, during the pioneering days of Canadian online journalism. From day one, we published no print edition and our local stories in that groundbreaking digital newspaper were updated on the fly throughout the day, but there were few bells and whistles, as very, very few of our online readers had cable broadband internet in 1996. Who remembers dial-up?

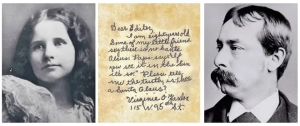

On Christmas Day 1996, I was called at home by a father who read us online and wondered if we could take a few minutes to put up the famous “Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus,” letter to the editor and the editorial response for his young daughter.

The letter and editorial had long been in the public domain. So we did. On Christmas Day.

Eight-year-old Virginia O’Hanlon wrote the long-ago letter to the editor of the New York Sun, and the quick response was printed as an unsigned editorial Sept. 21, 1897. The response of veteran newsman Francis Pharcellus Church has since become history’s most reprinted newspaper editorial.

A decade later, editing the Thompson Citizen and Nickel Belt News weekly newspapers here in Northern Manitoba, I resumed publishing the “Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus” letter to the editor from 2007 to 2013:

Dear Editor:

Please tell me the truth; is there a Santa Claus?

Virginia O’Hanlon

115 West Ninety-fifth Street

New York

In his editorial, Francis Pharcellus Church replied:

Virginia, your little friends are wrong. They have been affected by the skepticism of a skeptical age. They do not believe except [what] they see. They think that nothing can be which is not comprehensible by their little minds. All minds, Virginia, whether they be men’s or children’s, are little. In this great universe of ours man is a mere insect, an ant, in his intellect, as compared with the boundless world about him, as measured by the intelligence capable of grasping the whole of truth and knowledge.

Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus. He exists as certainly as love and generosity and devotion exist, and you know that they abound and give to your life its highest beauty and joy. Alas! How dreary would be the world if there were no Santa Claus. It would be as dreary as if there were no Virginias. There would be no childlike faith then, no poetry, no romance to make tolerable this existence. We should have no enjoyment, except in sense and sight. The eternal light with which childhood fills the world would be extinguished.

Not believe in Santa Claus! You might as well not believe in fairies! You might get your papa to hire men to watch in all the chimneys on Christmas Eve to catch Santa Claus, but even if they did not see Santa Claus coming down, what would that prove? Nobody sees Santa Claus, but that is no sign that there is no Santa Claus. The most real things in the world are those that neither children nor men can see. Did you ever see fairies dancing on the lawn? Of course not, but that’s no proof that they are not there. Nobody can conceive or imagine all the wonders there are unseen and unseeable in the world.

You may tear apart the baby’s rattle and see what makes the noise inside, but there is a veil covering the unseen world, which not the strongest man, nor even the united strength of all the strongest men that ever lived, could tear apart. Only faith, fancy, poetry, love, romance, can push aside that curtain and view and picture the supernal beauty and glory beyond. Is it all real? Ah, Virginia, in all this world there is nothing else real and abiding.

No Santa Claus! Thank God! He lives, and he lives forever. A thousand years from now, Virginia, nay, 10 times 10,000 years from now, he will continue to make glad the heart of childhood.

Above the reprinted editorial I would append a bold-faced and italicized introduction, which read:

“Editor’s note: Eight-year-old Virginia O’Hanlon wrote a letter to the editor of the New York Sun, and the quick response was printed as an unsigned editorial Sept. 21, 1897. The response of veteran newsman Francis Pharcellus Church has since become history’s most reprinted newspaper editorial. We, at the Thompson Citizen, are pleased to be part of that tradition and republishing it at Christmas has become an annual hallmark of the festive season for us here as well since Dec. 19, 2007. Merry Christmas, one and all.

John Barker.”

You can also read it in full here at: https://www.thompsoncitizen.net/opinion/editorial/yes-virginia-there-is-a-santa-claus-1.1367424

While at the Thompson Citizen and Nickel Belt News, I also much enjoyed re-printing for a number of years Garwood Robb’s “A special gift from years ago” as a guest “Soundings” column on the editorial page around Christmas:

“My first teaching assignment was in Thompson in 1968. Mary was a student of mine. She was from an extremely poor and dysfunctional family who lived on the edge of town about a quarter mile from the town’s railway station.

“On the last day of school before Christmas holidays many of the students brought me gifts. Mary never had any money and quite often came to school without lunch. The family was so poor that she shared boots and a winter coat with her brother. One day Alvin got to wear the coat, the next day Mary. For her to bring me a gift was special. It was small wrapped in Kleenex and tied with a piece of dirty string.

“When I opened it, there was a beautiful gold tie bar with a bright red ruby in the centre. In those days men had to wear suits and ties everyday to class. I thanked her for it while reassuring the other students that Mary had not stolen it. In actual fact she had; from the principal’s desk, the previous day.

“Mary was a loveable child, 12 years old in Grade 4. Students failed in those days and she had been held back several times. She lived with her mother and her two brothers, one older, one younger in a dilapidated weather-beaten shack. Money and food were always scarce for her family. Quite often I would see Mary begging for money on the street in front of the Thompson Inn on a Saturday night. After Christmas when I returned to Thompson I brought back a doll for Mary from Eaton’s. I secretly sent it home with her so the other girls in my class wouldn’t be jealous and so they wouldn’t say anything to hurt her. Mary had never had a doll and even at 12 that was all she wanted.

“The following winter while the children were home alone, fire destroyed Mary’s home in the middle of the night. Mary and her two siblings perished in the blaze.

“Every Christmas for nearly 40 years when I decorate our Christmas tree I unpack that gold tie bar with the red ruby and hang it in a very prominent place on the tree.

“Somewhere out there on Christmas night there is a shining star of a little girl who had a heart of gold but never had enough chances to show it.”

The column was first published in the Grandview Exponent, which serves the communities of Grandview and Gilbert Plains in the Parkland region of Manitoba, on Dec. 20, 2005, and later republished in Garwood Robb’s blog, “In My Own Words,” which is no longer available online at http://garwood2009.blogspot.ca/2009/12/memory-from-long-agorevisited.html but can still be read at https://www.thompsoncitizen.net/opinion/soundings-4274851

Garwood lived on Centennial Drive East in Thompson and taught at Westwood Elementary School from September 1968 to June 1972 when he moved to Winnipeg.

Two of my other favourite columns that would find their way into print at Christmas in the Thompson Citizen and Nickel Belt News were David J. Thompson’s “The night the lights were lit!,” which tells the story of Charles Dickens, A Christmas Carol, and the humble origins of the modern co-operative movement:

“On Dec. 21, 1844 the Rochdale Equitable Pioneers Society opened a small store in England with five items and little fanfare. Thus humbly began the modern co-operative movement. Let’s step back into that time to get a sense of how co-operative history was made.

“In the summer of 1843, a 31-year-old Charles Dickens journeyed to Lancashire, to see for himself how life was lived in the industrial north of England. To feed his insatiable journalistic curiosity, he visited a workhouse in Manchester to see how the poor were surviving the “hungry forties.” Dickens was taken aback by the terrible conditions he saw in the midst of the burgeoning wealth. In the bustling heartland of the Industrial Revolution he saw the two Englands of rich and poor.

“The next day, speaking to an audience of well-to-do aristocrats and mill owners at Manchester’s prestigious Athenaeum Club, he urged the audience to overcome their ignorance which he said was “the most prolific parent of misery and crime.” Dickens asked them to take action with the workers to “share a mutual duty and responsibility” to society. On the train back to London, impacted greatly by the poverty and misery he had seen, he conceptualized A Christmas Carol. He began writing the classic Christmas story a week later and completed it in six weeks. Since the book was published on Dec. 19, 1843, Christmas has never been the same.

“On the eve of revolutions throughout Europe, Dickens counselled that hearts must hear and eyes must see for society to change. In Dickens’ mind, the Bob Cratchits and Tiny Tims of the world would have to wait for the Ebenezer Scrooges to literally go through hell before heaven could be made upon Earth. Dickens later returned to the Lancashire mill towns to gather information for a later novel Hard Times. Dickens solution in much of his writing was the voluntary transformation of the rich and powerful.

“The winter solstice on Dec. 21 was the longest night of the year. Under the old Gregorian calendar, Dec. 21 was also Christmas Day. The co-op opened almost one year to the day after the publication of A Christmas Carol. However for the members of the newly formed co-op called the Rochdale Equitable Pioneers Society the holiday season would not be one of gifts or gaiety but of consternation and caution.

“On that Saturday night at 8 p.m., a small group of the Rochdale Pioneers and their families huddled together in the shop to witness the store’s opening. The temperature was below freezing made worse by the damp in the almost empty warehouse at 31 Toad Lane (T’Owd is dialect for the old Lane) in Rochdale. Outside on the busy lane they could hear the clattering of wooden clogs on the cobbled streets. The tired mill workers were hurrying home to find warmth from the winter’s chill. As the church bells across the street struck the appointed hour, the founding members heard each chime with beating hearts. Then, James Smithies went outside and bravely took the shutters off the windows. With the final shutter removed and a few candles bravely lighting the store’s bay windows the modern cooperative movement began. This little shop in Rochdale, England would be its lowly birthplace and these humble hard working families its founders.

Thompson’s column is also available online at: https://www.thompsoncitizen.net/opinion/the-night-the-lights-were-lit-4279065

The other column that I quite enjoyed reprinting was “The Gold and Ivory Tablecloth” by Howard C. Schade, the pastor between 1935 and 1940 of the Second Reformed Church in Coxsackie, New York, between the Catskill Mountains and Hudson River. “The Gold and “Ivory Tablecloth, perhaps more allegorical than literally true, was originally published in the December 1954 issue of Reader’s Digest magazine. Schade wrote:

“At Christmas time men and women everywhere gather in their churches to wonder anew at the greatest miracle the world has ever known. But the story I like best to recall was not a miracle, not exactly.

“It happened to a pastor who was very young. His church was very old. Once, long ago, it had flourished. Famous men had preached from its pulpit, prayed before its altar. Rich and poor alike had worshipped there and built it beautifully. Now the good days had passed from the section of town where it stood. But the pastor and his young wife believed in their run-down church. They felt that with paint, hammer, and faith they could get it in shape. Together they went to work.

“But late in December a severe storm whipped through the river valley, and the worst blow fell on the little church, a huge chunk of rain, soaked plaster fell out of the inside wall just behind the altar. Sorrowfully the pastor and his wife swept away the mess, but they couldn’t hide the ragged hole.

“The pastor looked at it and had to remind himself quickly. “Thy will be done!” But his wife wept, “Christmas is only two days away!”

“That afternoon the dispirited couple attended the auction held for the benefit of a youth group.

“The auctioneer opened a box and shook out of its folds a handsome gold and ivory lace tablecloth. It was a magnificent item, nearly 15 feet long, but it too, dated from a long vanished era. Who, today, had any use for such a thing? There were a few half-hearted bids. Then the pastor was seized with what he thought was a great idea.

“He bid it in for $6.50.

“Just before noon on the day of Christmas Eve, as the pastor was opening the church, he noticed a woman standing in the cold at the bus stop. “The bus won’t be here for 40 minutes!” he called, and invited her into the church to get warm.

“She told him that she had come from the city that morning to be interviewed for a job as governess to the children of one of the wealthy families in town but she had been turned down. A war refugee, her English was imperfect.

“The woman sat down in a pew and chafed her hands and rested. After a while she dropped her head and prayed. She looked up as the pastor began to adjust the great gold and ivory cloth across the hole. She rose suddenly and walked up the steps of the chancel. She looked at the tablecloth. The pastor smiled and started to tell her about the storm damage, but she didn’t seem to listen. She took up a fold of the cloth and rubbed it between her fingers.

“It is mine!” she said. “It is my banquet cloth!” She lifted up a corner and showed the surprised pastor that there were initials monogrammed on it. “My husband had the cloth made especially for me in Brussels! There could not be another like it.”

“For the next few minutes the woman and the pastor talked excitedly together. She explained that she was Viennese, that she and her husband had opposed the Nazis and decided to leave the country. They were advised to go separately. Her husband put her on a train for Switzerland. They planned that he would join her as soon as he could arrange to ship their household goods across the border. She never saw him again. Later she heard that he had died in a concentration camp.

“‘I have always felt that it was my fault, to leave without him,’ she said. “Perhaps these years of wandering have been my punishment!” The pastor tried to comfort her and urged her to take the cloth with her. She refused. Then she went away.

As the church began to fill on Christmas Eve, it was clear that the cloth was going to be a great success. It had been skillfully designed to look its best by candlelight.

After the service, the pastor stood at the doorway. Many people told him that the church looked beautiful. One gentle-faced middle-aged man, he was the local cloth and watch repairman, looked rather puzzled.

“It is strange,” he said in his soft accent. “Many years ago my wife, God rest her, and I owned such a cloth. In our home in Vienna, my wife put it on the table”, and here he smiled, “only when the bishop came to dinner.”

“The pastor suddenly became very excited. He told the jeweller about the woman who had been in church earlier that day. The started jeweller clutched the pastor’s arm. “Can it be? Does she live?”

“Together the two got in touch with the family who had interviewed her. Then, in the pastor’s car they started for the city. And as Christmas Day was born, this man and his wife, who had been separated through so many saddened Yuletides, were reunited.

“To all who hear this story, the joyful purpose of the storm that had knocked a hole in the wall of the church was now quite clear. Of course, people said it was a miracle, but I think you will agree it was the season for it!

“True love seems to find a way.”

Schade’s column is also available online at: https://www.thompsoncitizen.net/opinion/the-gold-and-ivory-tablecloth-4275996

You can also follow me on Twitter at: https://twitter.com/jwbarker22

.