My longtime friend, Paul Mason, from my first round of undergraduate days and nights at Trent University in Peterborough, Ontario from 1976 to 1979, wrote earlier today:

My longtime friend, Paul Mason, from my first round of undergraduate days and nights at Trent University in Peterborough, Ontario from 1976 to 1979, wrote earlier today:

“If I had the power to re-order university education in Ontario – and it’s probably just as well I haven’t – I would bring back university entrance exams. They would not measure whether students had mastered bodies of information, however, so much as whether they could read, write and reason: I’d confront them with four pieces of writing of some substance, and set them questions which sought to determine whether they had understood them, and whether they could say something intelligent about them. (And, yes, the pieces of writing could be delivered via audio file for those with learning disabilities, and their responses could be dictated.)

“Students would then embark on a two-year program designed to equip them with an Associate Degree. Each year would require them to take four courses: five is too many if students can reasonably be expected to do all the required readings. So in a Liberal Arts program, the first year course line-up might be, say, History, Politics, French and Biology; or English, Religious Studies, Geography and Astronomy; or Psychology, Sociology, Philosophy and Art History; or Music Theory, Calculus, Italian and Freshwater Ecosystems … But there would be strenuous encouragement for students to plunge into the extracurricular life of the university – singing in choirs, participating in theatrical productions, volunteering for after school childcare programs, playing a sport, attending public lectures in subjects outside their own disciplines.

“Students would then embark on a two-year program designed to equip them with an Associate Degree. Each year would require them to take four courses: five is too many if students can reasonably be expected to do all the required readings. So in a Liberal Arts program, the first year course line-up might be, say, History, Politics, French and Biology; or English, Religious Studies, Geography and Astronomy; or Psychology, Sociology, Philosophy and Art History; or Music Theory, Calculus, Italian and Freshwater Ecosystems … But there would be strenuous encouragement for students to plunge into the extracurricular life of the university – singing in choirs, participating in theatrical productions, volunteering for after school childcare programs, playing a sport, attending public lectures in subjects outside their own disciplines.

“Second year would permit greater specialization. And then – graduation! With an Associate Degree! And the university would say, go! Go out into the world! Work! Because now you’ve gained some independence from your families – or so one hopes – but you need to gain some life experience so that you have something to bring back, something to offer, when you convert your Associate Degree into an Honours BA. We’ll see you when you’re 25, 26, 27 – 30, even. We’ll see you when you have a better sense of who you are, and when you are able to better understand the value of what we’re offering you … and to have something to offer yourselves.”

“Yeah, I’m just thinking aloud. Interested, as always, to see what other folk have to say.”

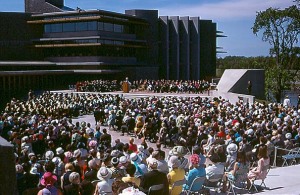

It took me almost 17 years to complete my Honours B.A. in History from Trent University between September 1976 and June 1993. When I arrived at Trent in 1976, I lived in Champlain College D-17, an upper floor single room on the staircase. There were co-ed washrooms on the winding staircase floors, and the sauna was co-ed. Colour me 19 years old in paradise. Did I say how much I came to like saunas? In deference to parental comfort, the dons helpfully made sure there were temporary paper signs designating “Mens” and “Womens” washrooms on the staircase for the September Sunday mom and dad delivered their first-year progeny to residence.

It was a very different time. To paraphrase the British writer, L.P. Hartley, the past is a foreign country and we did things differently there. The AIDS epidemic was still almost five years away and officially began on June 5, 1981, when the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in its Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report newsletter reported unusual clusters of Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) caused by a form of Pneumocystis carinii in five homosexual men in Los Angeles. Cecil County, Maryland bluegrass singer Zane Campbell’s haunting song Post-Mortem Bar in 1990, in the movie Longtime Companion, captured the poignancy of those days in the early 1980s when Campbell Scott, son of the legendary actor George C. Scott, and then a 28-year-old actor at the time, playing the character “Willy,” observed in the movie’s final scene, “It seems inconceivable, doesn’t it, that there was ever a time before this, when we didn’t wake up every day wondering who’s sick now, who else is gone?” as Post-Mortem Bar is heard in the background. If you read the comments from viewers on a YouTube clip linked to here you get some idea of the power of the ending and how some 25 years on it resonates with people still as the moment that AIDS was brought home for them and was no longer just a problem for some queers in San Francisco. You can listen to it and watch it on YouTube here at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dukIb4UU094

But the 80s were still in the future when I arrived at university as an undergraduate. There was a time before all this. In 1976, Bacchus ruled at Trent University.

As I finally walked across University Court in front of the Thomas J. Bata Library that convocation day in June 1993 to receive my four-year Honours B.A., and then Registrar Alf (A.O.C.) Cole was handing me my degree, then President and Vice-Chancellor John Stubbs, an historian by trade, grinned, shook my hand, and said to me, “Nice to see you finally take the walk.” Queen’s University in Kingston was a tad more formal in October 1995 when I received my master’s degree at the hands of Chancellor Agnes McCausland Benidickson. I had to kneel in front of her until she tapped me on the right shoulder, and spoke the words, “Rise, master of arts.” Fortunately, as a cradle Catholic, I had a deeply instilled love of ritual and tradition, which served me well that fall day.

I’m especially fond, however, of my 1992 three-year B.A. (Ordinary). What better reminder could one hope for in the academic world for instilling humility than a degree that has the word “ordinary” written on it? I think the three-year B.A. went from being an “Ordinary” at Trent to “General.” How prosaic. I’m not sure if a three-year B.A. by any name even exists any longer at Trent.

Technically you were supposed to “surrender” your three-year Ordinary B.A. to receive your four-year Honours B.A. If you’re looking down from the Great Registrar’s Office In-The-Sky, Alf, my apologies. I seem to have overlooked that at the time.

I really love some of the quirks of academic life. Marion Fry, in the Summer of 1978, when she was serving as acting president, had me in her office one morning to explain to me the finer distinctions between “rustication” and “debarment” (one year in academic exile, versus three for repeat offenders). The Committee on Undergraduate Standings and Petitions (CUSP) thought I was a worthy candidate for the former. Professor Fry, who just turned 90, and moved back to Peterborough after retiring as president and vice-chancellor of the University of King’s College in Halifax, the city where she was born, said to me at the time, “It’s not like we’d literally send you off in the wilderness for a year to be a rustic, John.”

I appealed the CUSP decision and the Special Appeals Committee, the impartial adjudicative appeal body of last resort for students on academic matters at Trent, overturned the CUSP decision and I carried on with my studies . My appeal, I thought, was based on a novel, albeit lame-sounding then and even now almost 44 years later argument: I had “failed” all five full-time courses for the 1977-78 academic year, true, but because I had not gone to almost any classes, and was then too busy with student politics and journalism to get myself over to the registrar’s office in time for the voluntary withdrawal deadline, I argued that my five Fs really said nothing about my academic ability in those particular circumstances, and shouldn’t be given too much weight. Certainly, not enough to rusticate me anyway. It is hard to imagine I delivered this argument before the committee in person with a straight face. Frankly, their more-than-generous verdict was a gift of unmerited grace, and I have been forever grateful. I was an indifferent student between 1976 and 1978, easily distracted from academics by student politics, the ARTHUR, Trent Radio, girls, parties, bootleg Molson Brador malt liquor from Hull, Québec, and Canadian Club rye whisky.

To this day, I believe, my Trent University permanent transcript notes I have five F’s from 1978 and an Ontario Graduate Scholarship (OGS) from 1993.

The role of the Special Appeals Committee “is to judge whether the application of university regulations, policies or practices has caused undue hardship on any student who appeals. Where undue hardship is found to have occurred, the committee has the authority to prescribe appropriate relief.” Jim Jury, a professor in the Physics Department, chaired the Special Appeals Committee at the time.

You can also follow me on Twitter at: https://twitter.com/jwbarker22