Only took one book out June 16 from the University College of the North’s (UCN) Wellington & Madeleine Spence Memorial Library on the Thompson campus, as it has been officially named since Aug. 25, and the place where I work for UCN, as I began my annual summer leave of absence – Don Gillmor’s novel Long Change, which was published last August.

Gillmor tells the story of Ritt Devlin, a Texan-turned-Canadian-turned-international oilman. Given that Long Change is due back Sept. 6, as am I, there’s nothing like a looming summer term loan deadline, I’ve found, to focus the mind. Sort of a derivation on Samuel Johnson’s famous quote, “When a man knows he is to be hanged … it concentrates his mind wonderfully” in reference to Anglican clergyman William Dodd, who was executed by hanging at England’s Tyburn Prison on June 27, 1777.

Long Change is a fine read so far. One of the early chapters, called “Mackenzie River, Northwest Territories, August, 1959” about a canoe trip up the river to the Mackenzie Delta, took me back to 2002 and Inuvik.

A year before Inuvik, I well I remember arriving in Yellowknife – and seeing rock outcroppings everywhere. I had never seen a place with so little grass that was so beautiful. Having moved from Halifax only a couple of weeks after being offered the job, I knew almost nothing about Canada’s North, save for a few Pierre Berton and Farley Mowat books I had read years before. So I was like a sponge soaking it all in. I’d come home from work that first October in 2001 to my apartment on the shores of Great Slave Lake, and read more and more of Bern Will Brown’s Arctic Journal and Arctic Journal II (a colleague had wisely recommended Brown’s writing as a good introduction to the Northwest Territories).

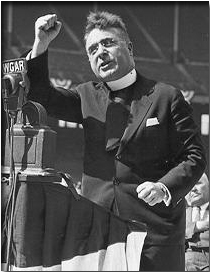

Brown, who died at his Sahtu home at the age of 94 in Colville Lake, a Hareskin Dene community, called Kiahba Mi Tuwe in Dene, in July 2014, over the course of his long life was a priest, a bush pilot, a dog musher, a painter, a journalist and a storyteller. He was born in Rochester, New York in 1920 and came to the Northwest Territories in 1948 as a priest with the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate. He built our Lady of the Snows log Roman Catholic Church in Colville Lake, which is 745 air kilometres northwest of Yellowknife, and ministered to a number of other remote First Nations communities in the Northwest Territories, northern Alberta and Saskatchewan, often travelling by dog team. He was laicized from the priesthood in 1971 and married Margaret Steen from Tuktoyaktuk.

After Brown left the priesthood, he became a bush pilot. Along with Margaret, they established Colville Lake Lodge, a hunting and fishing resort.

Gillmor’s novel Long Change, set between 1951 and 2014, has some overlap in time and place with the world of the real life Brown. The fictional Ritt Devlin may have got his start on the oil rigs of West Texas at the tender age of 15, but a few years later he will be working in the oilfields around Leduc, Alberta, and once there looking ever further north to the geological oil and gas bounty of the Mackenzie River, Mackenzie Valley and Mackenzie Delta, North of 6o in the Northwest Territories.

During my time living in the Northwest Territories from July 2001 to October 2003, diamonds were the new play in the Western Arctic and the long-delayed $16.2-billion proposed 1,196-kilometre natural gas pipeline system, known as the Mackenzie Gas Project, a partnership consortium that currently consists of Imperial Oil, the Aboriginal Pipeline Group (APG), ConocoPhillips Canada, Shell Canada and Exxon Mobil Corporation: a long-deferred dream for many; a nightmare for others. In 1974, Justice Tom Berger, a Supreme Court of British Columbia trial division judge, began hearings for what would become the famous Mackenzie Valley Pipeline Inquiry. After travelling to more than 30 communities across the territory, Berger recommended a 10-year moratorium on the Mackenzie Valley part of the project – until land claims were settled and environmental protections were in place – and a complete halt to any pipeline building across the northern Yukon.

While Gillmor’s protagonist is an oilman, the game in the oil patch isn’t so very different than it is for any of us who earn our livelihood’s in any of the assorted and sundry natural resources extraction towns that dot the seemingly never-ending landscape of Canada’s North. I well remember July 12, 2001, flying north on First Air from Edmonton to Yellowknife for the first time, looking down at the countless lakes and tundra with the unwilling-to-set midnight sun still above the western horizon when Yellowknife finally appeared below after 11 p.m. that Arctic Summer Thursday night.

While we may not work directly in the oil patch, or underground in a gold or nickel mine, our jobs – be it in journalism, social services, healthcare, fast food, hotel hospitality, retail, you name it – exist, for the most part, because of those who do work pulling oil or hauling gold or nickel out of the ground. That’s why we’re here. That’s the raison d’etre for Fort McMurray, Yellowknife and Thompson, Manitoba’s existence. I have spent 11 of the last 16 years since the millennium living in mining towns. I’ve been down to the 4,200-level at Vale’s Birchtree Mine and up to the top in the hoistroom in Thompson and rode a man-car along the underground rail-track to the bottom of Con Mine in Yellowknife – the first gold mine to go into production in the Northwest Territories in 1938 – during its last days in 2003.

But take away the oil, gold and nickel and there’s not much reason for these towns to exist, all mindless happy talk from politicians, newspaper publishers and other spin doctors aside.

It is a lesson being re-learned again, painfully, as history repeats itself for those with no memory apparently, in Northern Manitoba this summer.

On Aug. 22, Tolko Industries said they were going to pull the plug on their heavy-duty kraft paper and lumber mill in The Pas after 19 years.

Vernon, British Columbia-based Tolko, the largest employer in The Pas, will close the Northern Manitoba mill Dec. 2, leaving all 332 employees unemployed.

The mill in The Pas has been a money-loser for years. It was conceived by the Progressive Conservative provincial government of premier Duff Roblin in 1966. The Tories struck a deal with Austrian businessman Alexander Kasser to create Churchill Forest Industries, the company that built the mill in 1966. With little oversight bout $93 million flowed from the Province of Manitoba into Churchill Forest Industries.

The Manitoba government pursued Kasser in an attempt to recoup around $30 million that he had taken from the company, but eventually settled in 1983, with Kasser pleading guilty to theft over $200 and paying $1 million in fines. The province dropped 34 related charges.

Then NDP premier Ed Schreyer called the affair the “blackest moment in Manitoba’s economic history.”

Churchill Forest Industries was the subject of a commission of inquiry that found a number of cabinet ministers, civil servants, lawyers and economic consultants failed to recognize and stop Kasser’s fraud.

In response to the fraud investigation, Manitoba took over the mill in 1973.

It was then managed by Manfor, a provincial Crown corporation, from 1973 to 1988. During this time, Manfor lost $300 million.

Tolko’s predecessor, Repap Enterprises, bought the facility in 1989 for $132 million. Less than 10 years later, it sold the mill to Tolko for $47 million.

In 2006, Tolko threatened to close. Premier Gary Doer’s NDP government responded by providing millions in financial stabilization aid to help keep the mill running.

Four years later in 2010, when the mill was facing slumping demand for Canadian lumber in the United States, the Harper Conservative government gave Tolko Industries $2.26 million in federal monies to improve its energy efficiency under the pulp and paper green transformation program. Six years after that, Tolko pulled the plug.

Less than a month before Tolko pulled the plug on its mill in The Pas, OmniTRAX, the Denver-based short line railroad, which owns the Port of Churchill, announced on July 25 it would be laying off or not re-hiring about 90 port workers, as it was cancelling the 2016 grain shipping season. At the time the cancellation was announced near the end of July, OmniTRAX did not have a single committed grain shipping contract. Normally, the Port of Churchill has a 14-week shipping season from July 15 to Oct. 31.

OmniTRAX bought most of Northern Manitoba’s rail track from The Pas to Churchill in 1997 from CN for $11 million. The track reached Churchill on March 29, 1929. The last spike, wrapped in tinfoil ripped from a packet of tobacco, was hammered in to mark completion of the project: an iron spike in silver ceremonial trappings. OmniTRAX took over the related Port of Churchill, which opened in 1929, when it acquired it from Canada Ports Corporation, for a token $10 soon after buying the rail line. The Port of Churchill has the largest fuel terminal in the Arctic and is North America’s only deep water Arctic seaport that offers a gateway between North America and Mexico, South America, Europe and the Middle East. OmniTRAX created Hudson Bay Railway in 1997, the same year it took over operation of the Port of Churchill. It operates 820 kilometres of track in Manitoba between The Pas and Churchill.

OmniTRAX had a terrible grain shipping season through Canada’s most northerly grain and oilseeds export terminal last year, moving only 184,600 tonnes as compared to 540,000 tonnes in 2014 and 640,000 tonnes in 2013. In 1977 an all-time record 816,000 tonnes were shipped from the Port of Churchill. OmniTRAX is on a Canadian National (CN) interchange at The Pas and relies on CN for the grain-filled cars. OmniTRAX considered 500,000 tonnes a normal shipping season. Wheat accounts for most of the grain loaded in Churchill, with some durum and canola also being shipped. In addition to grain and oil seeds, the shipping season has also included vessels loaded with re-supply shipments, such as petroleum products, northbound for Nunavut.

OmniTRAX moved between 2011 and 2014 to diversify the commodity mix the railway and port handle here in Manitoba in the wake of the federal government legislating the end of the Canadian Wheat Board’s grain monopoly, creating a new grain market. OmniTRAX said at the time transporting just grain would not be enough to sustain their Manitoba business over the longer term. The Canadian Wheat Board, renamed G3 Canada Ltd. by its new owners, has built a network of grain elevators, terminals and vessels that bypasses Churchill and uses the Great Lakes, St. Lawrence River and West Coast to move grain to foreign markets.

In 2013, worried about the viability of relying primarily on grain shipments through Churchill, OmniTRAX unveiled plans to ship Bakken and Western Intermediate sweet crude oil bound for markets in eastern North America and Western Europe on 80-tanker car Hudson Bay Railway trains from The Pas to Churchill and then from the Port of Churchill on Panamax-class tanker ships out Hudson Bay, the world’s largest seasonally ice-covered inland sea, stretching 1,500 kilometres at its widest extent, to markets in eastern North America and Western Europe.

However, the oil-by-rail to Churchill plan, unveiled in Thompson on Aug, 15, 2013, met a firestorm of public opposition, ranging from local citizens, members of First Nations aboriginal communities along the Bayline between Gillam and Churchill, with whistle stops in places like Bird, Sundance Amery, Charlebois, Weir River, Lawledge, Thibaudeau, Silcox, Herchmer, Kellett, O’Day, Back, McClintock, Cromarty, Belcher, Chesnaye, Lamprey, Bylot, Digges, Tidal and Fort Churchill, environmental activists, including the Wilderness Committee’s Manitoba Field Office, and even government officials – opposition fueled in part no doubt by the tragedy only 5½ weeks earlier at Lac-Mégantic, Québec where a runaway Montreal, Maine & Atlantic Railway (MMA) freight train carrying crude oil from the Bakken shale gas formation in North Dakota – in 72 CTC-111A tanker cars – derailed in downtown Lac-Mégantic in Quebec’s Eastern Townships on July 6, 2013. Forty-seven people died as a result of the fiery explosion that followed the derailment.

Within a year, OmniTRAX shelved its oil-by-rail shipping plan from The Pas to Churchill in August 2014. OmniTRAX accepted a letter of intent last December from Mathias Colomb First Nation, Tataskweyak Cree Nation and the War Lake First Nation to buy its rail assets in Manitoba, along with the Port of Churchill, but the deal has not been completed to date, and its future looks murky to non-existent.

You can also follow me on Twitter at: https://twitter.com/jwbarker22