I never worked directly for Jimmy Carter. In fact, I have never met him, unlike my friend Art Milnes, a journalist from Kingston, Ontario, who would years later become a cherished personal friend of Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter. But I did spend the last 2½ months of the 1980 Jimmy Carter presidential re-election campaign working as a supervisor for Cambridge Survey Research, where I oversaw several hundred phone bank employees for Democratic National Committee (DNC) pollster Pat Caddell’s firm in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Most of our work that autumn was on the Carter campaign and U.S. Senate races.

I was 23 years old and had just moved to West Somerville, Massachusetts and was looking for a job in September 1980. I happened to be walking down the west side of Massachusetts Avenue, near Central Square in Cambridge, on a sunny, but crisp, late summer Boston morning, when I saw a help wanted job ad for interviewers down in a hole-in the-wall basement commercial space below sidewalk level.

I spent my first two days working the phones, polling voters state-by-state. I was then promoted to supervise phone bank interviewers. I remember thinking there apparently really is something to the American Story of meritocracy. My only previous experience in public opinion research had been working a few months earlier in the spring of 1980 on a Quebec Referendum project for a Winnipeg company, Opinion Place/Marketing Insights, as a field interviewer in Peterborough, Ontario for the Center for Canadian Studies at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina.

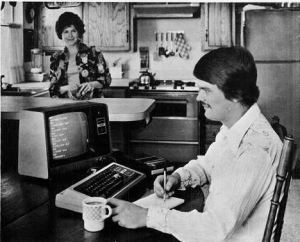

My Cambridge Survey Research boss, Mark Leavitt, took me out to my first Boston Red Sox game at Fenway Park to celebrate my promotion. I still remember his pre-game advice: “Make sure there is a full aspirin bottle by the coffeemaker for employees.” Back then, sampling was done with actual physical telephone directories and coding was done largely by hand. One of the curiosities I quickly noticed was that our ASA-and-caffeine-driven phone bank interviewers, if they spent more than a a couple of days working a region, would fairly quickly wind up sounding like the respondents from whatever area code they were calling and interviewing people on their political preferences, especially in smaller and more ethnically homogenous areas of the country. Some kid from Jersey would wind up talking slower and softer, like he was from the lowcountry of South Carolina, after a few days. By far the most difficult voters to reach were those who had telephone numbers in the hollers of Tennessee and Kentucky. You could call 100 numbers and 99 would be unreachable because of some technical glitch, or simply out of service.

While we knew we were in an uphill re-election battle against Republican challenger Ronald Reagan, I don’t think it was until the last days of the campaign, when we realized there would be no “October Surprise” with the release of the 52 United States diplomats and American citizens being held hostage by Iranian students in Tehran, that we also realized we were going to come up short on election day Nov. 4.

We lost the election. Big time. I well remember going to work a few days after, late in the afternoon, riding above ground aboard a subway car on the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) Red Line “T”. The November sky was a foreboding steel-gray, with leaves all fallen now from the trees. And there it was, as we headed into Harvard Yard, giant spray –painted graffiti on a cenotaph proclaiming “Ray-Gun” had been elected.

After the Carter campaign, I went to work as research associate at Kenyon and Eckhardt (later Bozell, Jacobs, Kenyon and Eckhardt) in Boston. I worked in the research department of the advertising agency’s Boston field office. Major commercial client accounts included airline and automotive companies.

As it turned out, Reagan did have a fondness for his Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), nicknamed Star Wars. But the dreamed-for global missile shield didn’t come to fruition. Instead, Reagan, along with Mikhail Gorbachev, general secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, managed to end the Cold War with perestroika [restructuring] and glasnost [openness] becoming part of the everyday vocabulary of Americans by the late 1980s, rolling from their tongues as if they had been saying the two Russian words forever.

As for Jimmy Carter, well, he would go on to become the most consequential and respected former president in United States history. At 98, he is also the oldest-ever former president.

Millard Fuller founded Habitat for Humanity International in 1976. From humble beginnings in Alabama, he rose to become a self-made marketing millionaire at 29. But as the business prospered, his health, integrity and marriage suffered, he noted later. In 1965, Millard and his wife Linda turned away from their millionaire lifestyle and rededicated their lives to serving God.

Jimmy Carter and his wife, Rosalynn, remain the best-known faces of Habitat for Humanity. Their involvement began in 1984 when the former president led a work group to New York City to help renovate a six-story building with 19 families in need of decent, affordable shelter.

A non-profit, ecumenical Christian housing ministry, Habitat for Humanity seeks to eliminate poverty housing and homelessness and to make decent shelter a matter of conscience and action.

Through volunteer labour and donations of money and materials, Habitat builds and rehabilitates simple, decent houses alongside the homeowner partner families. It is not a giveaway program. In addition to a down payment and monthly mortgage payments, homeowners invest hundreds of hours of their own labour or sweat equity into building their Habitat house and the houses of others. Habitat houses are sold to partner families at no profit and financed with affordable loans. The homeowners’ monthly mortgage payments are used to build still more Habitat houses.

Jimmy Carter is not only finishing well. He started well.

“For myself and for our Nation, I want to thank my predecessor for all he has done to heal our land.”

You can also follow me on Twitter at: https://twitter.com/jwbarker22