In the Great Pizza debate there is really only one main question: Is Hawaiian pizza a delight or an abomination?

In the Great Pizza debate there is really only one main question: Is Hawaiian pizza a delight or an abomination?

Sure, there are some subsidiary questions connoisseurs ask about, such as whether anthracite coal-fired or wood-fired ovens bakes a better pizza pie, although it’s a bit of an apples and oranges comparison because the answer partly depends on the kind of cheese topping and other ingredients, or whether the best pizzas in North America come out of a handful of pizza joints in New York City or New Haven, Connecticut? That sort of thing.

Coal-fired ovens typically run between 800°F and 1,000°F, sometimes even higher, according to Pizza Today, the industry’s leading trade magazine, which was launched in 1984 by pizzeria owner Gerry Durnell in the tiny town of Santa Claus, Indiana.

Durnell had worked his way through college as a rock and roll disc jokey, a TV cameraman, and as an announcer for the Ozark Jubilee. He was running an ice cream shop in Santa Claus, in southwestern Indiana, not too far from the Kentucky state line , when he decided to add baking pizzas to his restaurant menu.

In a Dec. 15, 2104 article in Pizza Today, headlined “Respecting the Craft: Wood vs. Coal,” Tony Gemignani, who got his start in 1991 as a pizza thrower at his brother’s Pyzano’s Pizzeria in Castro Valley, California, notes “specialty cheese like a dry mozzarella, also known as a Caprese loaf, is common. This cheese is typically sliced and applied before the sauce. Common pizzas are tomato pies, clam and garlic, and sausage, says Gemignani, the first and only Triple Crown winner to date for baking at the International Pizza Championships in Lecce, Italy. “When you’re cooking at such a high temperature, even higher than a wood-fired oven,” he says, “you still have a longer bake time because a coal oven doesn’t have a high flame like a wood-fired oven. The pizza is typically 16 to 18 inches in diameter and is charred yet pliable. It has a slight crispness, with some stability.

“A wood-fired oven typically runs between 650°F and 900°F. At 900°F, pizzas can cook in 60 to 90 seconds. Fresh mozzarella and buffalo mozz are typically used. The pizzas that come from these ovens are typically 11 to 13 inches in diameter and come out of the ovens charred, soft, delicate and sometimes wet (even soupy at times). They are not recommended for delivery.

“When it comes to the price of wood and coal, they are very similar.”

Lombardi’s (a favourite of Italian tenor Enrico Caruso) was founded in 1905 on Spring Street in the Little Italy section of Manhattan in New York City, and is the oldest pizzeria in the United States. While it is generally agreed pizza originated in Italy, the date of its invention is hard to pin down with exactitude.

Neapolitan pizza is first mentioned by name in the late 18th century, and that’s usually considered to be the origin date for pizza, but a minority opinion in recent years is that pizza dates back to 997 in the 10th century, when it appears on a Latin list of foods to be supplied annually at Christmas and Easter as a tithe to the archbishops of Gaeta (“whether to us or our successors”) in central Italy, payable by the tenants of a mill on the nearby Garigliano River.

In support of the later Naples origins of pizza theory, an often recounted story holds that on June 11, 1889, to honour the Queen consort of Italy, Margherita of Savoy, the Neapolitan pizza-maker Raffaele Esposito created the “Pizza Margherita”, a pizza garnished with tomatoes, mozzarella, and basil, to represent the national colours of Italy as on the Italian flag.

Carol Helstosky, an associate professor of history at the University of Denver, and the author of Pizza: A Global History, told CBC Radio earlier this year that “pizza never had that great a reputation throughout much of its history. As people tried pizza, it had its origins in Naples, right, in the 17th century. And as people outside of Naples, even other Italians or foreigners, tried pizza they reacted with absolute disgust. I believe American inventor Samuel Morse, when he visited Naples and tried pizza, he described that as a type of ‘nauseous cake.'”

In Naples, Helstosky says, there were several different types of pizza, but “mostly pizza was consumed by the poorest of the Neapolitans – soldiers, workers, families who didn’t have access to kitchens and purchased cheap street food. This was also a place where people could eat pasta street side, and so pizza would be a cheap takeaway snack. And so the pizzaiolo would make pizza out of whatever ingredients he happened to have on hand. Near Naples, tomatoes were certainly popular but also fish. And then some mozzarella made out of buffalo milk, fresh herbs like basil or oregano. Whatever was on hand would be sprinkled on top of a pizza.”

Morse, who hardly tried to telegraph his opinion on the matter, apparently was of a minority view on the subject of pizza, which in the 21st century is, if not quite a universal dish worldwide, well, at least and international dish. In March 2015, Pope Francis told Valentina Alazraki, the veteran Vatican correspondent for Mexico’s Noticieros Televisa, the only thing he really missed after two years as pope was the ability “to go out to a pizzeria and eat a pizza,” adding that even as Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio in Buenos Aires he was free to roam the streets, particularly to visit parishes (https://soundingsjohnbarker.wordpress.com/2015/03/15/catholic-cooking-from-pope-francis-love-for-buenos-aires-pizzerias-to-father-leo-patalinghug-the-tv-show-filipino-cooking-priest/).

Almost half the population of Buenos Aires can rightfully claim Italian heritage, so it is little surprise the Argentinian capital is so well-known for its Napoletana pizza. “The only thing I would like is to go out one day, without being recognized, and go to a pizzeria for a pizza,” Pope Francis said, comparing his life now to how it was when he was Archbishop of Buenos Aires. “In Buenos Aires I was a rover. I moved between parishes and certainly this habit has changed. It has been hard work to change. But you get used to it,” Pope Francis told Alazraki.

Last year I wrote about Glenview, Illinois-based Family Video (https://soundingsjohnbarker.wordpress.com/2016/01/17/who-shot-the-video-store-and-how-did-glenview-illinois-based-family-video-survive-to-thrive-and-still-rent-movies-and-now-sell-pizza/), which continues to survive and thrive and still rent movies, but also mentioned how they now sell pizza made in their video stores from Marco’s Pizza of Toledo, Ohio. Marco’s Pizza, founded in 1978 by Pasquale “Pat” Giammarco, is one of the fastest-growing pizza franchise operations in the United States. The Toledo-based delivery pizza franchisor opened 116 stores in 2015. Pizza is a $46- billion market in the United States that continues to grow at a rate of about one to two per cent per year.

I’ve written here and elsewhere about driving a Plymouth Duster to deliver for Mother’s Pizza Simcoe North in Oshawa during my last spring in high school for $2.65 per hour – plus tips (https://soundingsjohnbarker.wordpress.com/2014/09/15/a-taste-for-yesterday-mothers-pizza-and-pepis-pizza/). Mother’s was an iconic Canadian pizza parlour chain from the 1970s – with its swinging parlour-style doors, Tiffany lamps, antique-style chairs, red-and-white checked gingham tablecloths, black-and-white short silent movies shown on a screen for patrons waiting for their meal to enjoy, root beer floats and pizzas served on silver-coloured metal pedestal stands.

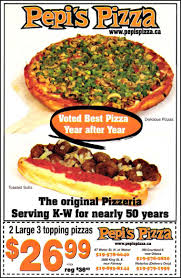

I also recall writing on Oshawa’s “Share Your Memories” webpage that “in keeping with the spirit of the thing, my own comment Feb. 3 [2014] reads, ‘Pepi’s Pizza, eh? Simcoe and John streets. I had a friend who worked there circa 1973-74. I still have fond memories of the pepperoni pizza … greasy, yes, sure. But superb also.’”

Mother’s Pizza was founded in 1970 by three partners, Grey Sisson, Ken Fowler and Pasquale Marra, and got its start in the Westdale Village area of Steeltown. The chain eventually grew to about 120 locations in Canada, the United States and England.

In 2008, Brian Alger acquired the then-expired trademark to Mother’s Pizza – one of his favourite childhood brands – and along with another entrepreneur, Geeve Sandhu, re-opened April 1, 2013 at 701 Queenston Rd. in Hamilton, Ont.

When Sam Panopoulos emigrated, along with his two brothers, when he was 20, from Greece to Canada in 1954, pizza was an oddity. “Pizza wasn’t in Canada – nowhere,” he told CBC Radio’s As It Happens last February.

“At the time, the food was available in Detroit and was slowly making its way to neighbouring Windsor, Ont., not far from Chatham, Ont., the small town where Panopoulos had settled and opened a restaurant,” CBC reported.

“When visiting Windsor, he dined on pizza and decided to try making it at home. ‘Those days, the main thing was mushrooms, bacon and pepperoni. There was nothing else going on the pizza,'” said Panopoulos.

“Inspired by a can of pineapple on his shelf, he took a chance and tossed the fruit on his pizza. The year was 1962. Hawaiian pizza had arrived at the Satellite Restaurant in Chatham.

“We just put it on, just for the fun of it, see how it was going to taste,” Panopoulos told the BBC News last February. “We were young in the business and we were doing a lot of experiments.

“Customers ended up loving the savoury sweetness of the dish.

“The creation also capitalized on the mid-century tiki trend, which popularized Polynesian culture in North America.

“Nobody liked it at first,” said Panopoulos. “Those days nobody was mixing sweets and sours and all that. It was plain, plain food.”

That debate continues 55 years later. Icelandic President Guðni Th. Jóhannesson made world headlines earlier this year at a university in Iceland, in a story that became known as “Pineapplegate” after he was asked whimsical question about his views on pineapple as a topping on pizza and he responded in a lighthearted way that he thought that it should be banned and that he was “fundamentally opposed” to pineapple on pizza and suggested. “I like pineapple, just not on pizza. But I can’t make laws that make it illegal for people to put pineapples on their pizzas,” Guðni said. “I am happy I don’t have that authority, presidents shouldn’t be tyrants. I wouldn’t want to live in a world where those in my position could ban things they don’t like. But I recommend putting seafood on pizza.”

Sam Panopoulos, who was 83, died last month. “From what I have read, Sam was a decent man with a good sense of humour,” Guðni wrote on Facebook. “Indirectly you could say we crossed paths after I jokingly (yeah, right) said that this particular topping should be banned.”

Me? Well, I don’t know that I tried any kind of pizza until maybe the early 1970s when I was 13 or 14. My parents came a bit late to the appeal of pizza, although I do recall my dad heading out on the occasional Friday night when some of my Nipigon Street friends, perhaps Mike Byrne and Paul Sobanski, were over, and dad coming back with a box of Mothers Pizza from Simcoe North, the first and only Mothers in Oshawa at the time.

I think I may have had my first Hawaiian pizza in the late spring or early summer of 1976, at the very, very end of my Oshawa Catholic High School Grade 13 days, on a picnic table at Lakeview Park in the south end of Oshawa on the north shore of Lake Ontario, hanging out in those last glorious days of high school freedom with my comrades in numerous adventures, both big and small, Ann Marie (a.k.a. Annie and A.M.) McDermott, and Gerry Byrne, both of whom are friends to this day. I might even have been just finishing up my part-time after-school driving job for Mothers Pizza Simcoe North at the time, as I got ready to move to a higher-paying student summer job at General Motors of Canada, before beginning my higher learning at Trent University in Peterborough, Ontario that September.

The Hawaiian pizza verdict? Well, last night I had both chunks of pineapple and anchovies’ paste on the pizza I constructed at home (pictured above), suggesting I’m quite OK with mixing sweets and sours, and enjoy the savoury sweetness of the Hawaiian pizza model (I tend to improvise a bit) that Sam Panopoulos first offered us in 1962 at his Satellite Restaurant in Chatham.

Thanks, and aloha, Sam!

You can also follow me on Twitter at: https://twitter.com/jwbarker22

Burger Chef. All but forgotten today. I only had a few opportunities to sample their cuisine when they had locations I would occasionally pass by on downtown pavement ribbons in places such as Oshawa, Ontario and Brattleboro, Vermont, sometimes just looking for a quick fast-food pit stop on my Honda motorcycle in those days before my Chevrolet Vega, when I would night ride with no windshield but an electric start at least, through the rugged Green Mountains of southern Vermont and pick up a Big Chef (also known as a Big Shef) burger in Brattleboro, if I hadn’t already 70 miles earlier in the far eastern Adirondack Mountains reaches of New York State savored one of the last remaining Red Barn “Big Barney” or “Barnbuster” burgers I could find along a mountainous two-lane stretch of U.S. Route 7, a road that was part of the original plan for the United States highway system approved by the Bureau of Public Roads in November 1926, up in the Adirondacks in Troy, in Rensselaer County, 30 miles from the Vermont state line and the Green Mountains.

Burger Chef. All but forgotten today. I only had a few opportunities to sample their cuisine when they had locations I would occasionally pass by on downtown pavement ribbons in places such as Oshawa, Ontario and Brattleboro, Vermont, sometimes just looking for a quick fast-food pit stop on my Honda motorcycle in those days before my Chevrolet Vega, when I would night ride with no windshield but an electric start at least, through the rugged Green Mountains of southern Vermont and pick up a Big Chef (also known as a Big Shef) burger in Brattleboro, if I hadn’t already 70 miles earlier in the far eastern Adirondack Mountains reaches of New York State savored one of the last remaining Red Barn “Big Barney” or “Barnbuster” burgers I could find along a mountainous two-lane stretch of U.S. Route 7, a road that was part of the original plan for the United States highway system approved by the Bureau of Public Roads in November 1926, up in the Adirondacks in Troy, in Rensselaer County, 30 miles from the Vermont state line and the Green Mountains.