OK … we’ve all heard the phrase “fishwrap” applied derogatorily by critics assessing the quality of newspapers wherever they live from time to time. Methinks some weeks that does a disservice to how my favourite pickerel from Paint Lake should be treated, but it isn’t just local newspapers that are problematically bad at times. Take the venerable Associated Press, affectionately known by working journos simply as the AP. They managed to move this alert last Wednesday: “BC-APNewsAlert/17. New York Yankees Hall of Fame catcher Yogi Bear has died. He was 90.” Actually, Yogi Bear, the beloved Hanna-Barbera cartoon character is only 57. He was created in 1958, making his début as a supporting character in The Huckleberry Hound Show, and was the first breakout character created by Hanna-Barbera and was eventually more popular than Huckleberry Hound.

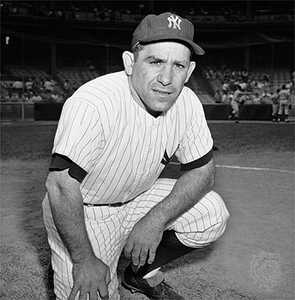

Yogi Berra, the beloved baseball player, on the other hand, was created in 1924 and born in 1925. A native of St. Louis, Berra signed with the New York Yankees in 1943 before serving in the U.S. Navy in the Second World War. He made his major league début in 1946 and was a stalwart in the Yankees’ lineup during the team’s championship years in the 1940s and 1950s.

Berra was a power hitter and strong defensive catcher. He caught Yankees’ pitcher Don Larsen’s perfect game on Oct. 8, 1956, in Game 5 of the 1956 World Series against the Brooklyn Dodgers, the only perfect game in Major League Baseball (MLB) post-season history. After playing 18 seasons with the Yankees, Berra retired following the 1963 season. Berra was also famous for his string of truisms, tautologies and malapropisms, including “Nobody goes there any more; it’s too crowded,” along with, “It ain’t over til it’s over” or, “Anyone who is popular is bound to be disliked,” as well as, “Half the lies they tell about me aren’t true” and, “If you ask me anything I don’t know, I’m not going to answer.” My personal favourite, which I managed to inject into several columns, editorials or news stories over the years, was the well-known, “This is like déjà vu all over again,” which I had used again as recently as Aug. 24, less than a month before Yogi Berra died.

It was while I was pondering how a boo boo like the Yogi Bear/Yogi Berra obituary mix-up happens in journalism (I suspect the eagle-eyed Ranger John Francis Smith from Jellystone Park would have known the difference) that I came across the latest information on robo-journalism (not to be mixed up with Tory robo-calls during the 2011 federal election campaign, I should point out to my friends still remaining in Canadian journalism.) Turns out that unlike most human journalists, who are for the most part seriously mathematically challenged, robot journalists that already work for such illustrious newspapers as the New York Times and Los Angeles Times, as well as Forbes, the storied business magazine, have shown a natural aptitude for data, making them ideal for the sports and business desks, and as such are now about ready to branch out into breaking news and investigative journalism.

Neil Sharman (believed to be a human writer) and former head of research and insight at Telegraph Media Group on Buckingham Palace Road in London, writing Sept. 22 in TheMediaBriefing, also based in London, noted that robots, “Like junior reporters … can learn from and draw on a back catalogue of great writing – but with more powerful memories and analytical techniques.” You can read Sharman’s full piece here: http://www.themediabriefing.com/article/robo-journalism-the-future-is-arriving-quickly

“Machines are adept at investigating data sets,” Sharman says. “Publishers have set them to tax records, homicide data, meteorological reports and more –looking for patterns and describing them. They’re thorough, not prone to error and they’re fast.

“The LA Times uses robo-journalism to break news about earthquakes because machines can analyse geological survey data faster than a human. It takes under five minutes to spot a story and get it online.”

Tim Adams, a staff writer for the “The Observer: The New Review” at London’s The Guardian newspaper, wrote a piece June 28 on Kris Hammond, a professor of journalism and computer science at Northwestern University and co-founder and chief scientist at Chicago-based Narrative Science, which developed a writing program for robots known as “Quill.” Hammond also founded the University of Chicago’s Artificial Intelligence Laboratory. He told Adams, “we are humanizing the machine and giving it the ability not only to look at data but, based on general ideas of what is important and a close understanding of who the audience is, we are giving it the tools to know how to tell us stories.”

Adams observes, “It’s not deathless prose – at least not yet; the machines are still ‘learning’ day by day how to write effectively – but it’s already good enough to replace the jobs once done by wire reporters. Narrative Science’s computers provide daily market reports for Forbes as well sports reports for the Big Ten sports network. Hammond predicts that 90 per cent of journalism will be written by computer by 2030. Automated Insights, one of Narrative Sciences competitors, based in Durham, North Carolina, does all the data-based stock reports for AP.

Adams also notes that “last year, a Swedish media professor, Christer Clerwall, conducted the first proper blind study into how sports reports written by computers and by humans compared. Readers taking part in the study suggested, on the whole, that the reports written by human sports journalists were slightly more accessible and enjoyable, but that those written by computer seemed a little more informative and trustworthy.”

Clerwall, an assistant professor in media and communication studies at Karlstad University in Karlstad, Sweden concluded that “perhaps the most interesting result in the study is that there are [almost] no… significant differences in how the two texts are perceived.”

In terms of narrative arcs, Hammond says, “Like any decent hack, the machine is coming to learn that there are only five or six compelling tales available: back from the brink, outrageous fortune, sudden catastrophe and so on.”

You can also follow me on Twitter at: https://twitter.com/jwbarker22