On Sept 21, 2013, I received a three-sentence e-mail from a reader out of the blue saying, “I just read your article on James Macdonald. I would never want to disrespect the deceased/missing, but he fits the description of Dan Cooper. The FBI suspects D.B. Cooper was from Canada.”

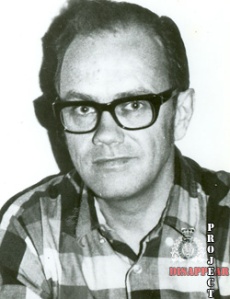

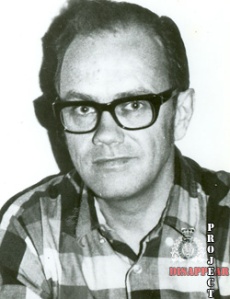

The Dec. 7, 2012 story he referred to was about James (Jim) Hugh Macdonald, 46, the owner of J.H. Macdonald & Associates Ltd., consulting structural engineers on Pembina Highway in Winnipeg, who climbed into his Mooney Mark M20D single-engine prop aircraft, bearing the registration mark CF-ABT, and took off half an hour after sunset from the Thompson Airport in Northern Manitoba at 4:30 p.m. on Dec. 7, 1971 to make his return flight home and disappeared into the rapidly darkening sky to never be seen or heard from again. He was the sole occupant of the four-seater plane.

To this day, the Winnipeg private pilot and civil engineer, who would be 89 if he were still alive, is still listed by the RCMP as a “missing person,” as no remains or wreckage were ever found, and is featured on the website of “Project Disappear,” Manitoba’s missing person/cold case project managed by the RCMP “D” Division historical case and major case management units in Winnipeg at: http://www.macp.mb.ca/results.php?id=76. “The file is currently still under investigation and is with the RCMP “D” Division historical case unit,” retired Sgt. Line Karpish, then senior media relations spokesperson for the Mounties in Winnipeg, said Dec. 6, 2012. The file number for the Macdonald missing person case is File #: 1989-10514. Anyone with information on Macdonald’s disappearance almost 43 years ago is asked to call Winnipeg RCMP at (204) 983-5461 or contact them by email at: ddiv_contact@rcmp-grc.gc.ca

From the disappearance and still ongoing search for Malaysia Airlines Flight MH370, with 239 people aboard (227 passengers and 12 crew), which took off from Kuala Lumpur after midnight Malaysia Time (MYT) on March 8, never making it to its 6:30. a.m. scheduled arrival in Beijing, disappearing from civilian radar over the Gulf of Thailand as responsibility was being handed from Malaysian ground control to Vietnam, to an Argentine military plane carrying 69 people that disappeared in 1965 and has never been found, to Amelia Earhart in 1937 through the disappearance of Flight 19, the five United States Navy TBM Avenger Torpedo Bombers that went missing over the Bermuda Triangle in the Atlantic Ocean on Dec. 5, 1945, and then D.B. Cooper on Nov. 24, 1971 – just 2½ weeks before Macdonald disappeared – there has long been a huge public fascination with the mystery of missing aviators or similar aviation-related stories before Macdonald disappeared. His widow, Claire Macdonald, told me in an interview in December 2012 that someone once wildly jokingly said to her, “Maybe he flew to Mexico.” She said her reply was: “How far can you go in that little plane in that winter weather?” But the close nexus in time between the two aviation disappearances in late 1971 and the fact both men were Caucasians in their mid-forties made at least some Cooper and Macdonald comparisons inevitable.

J.H. Macdonald & Associates Ltd. was a small firm with about seven employees. Jim Macdonald was the only professional engineer on staff and a few months after his disappearance, its business affairs were wound down.

One of Macdonald’s last projects as a consulting structural engineer was the construction of additional classroom space for special needs students at Prince Charles School on Wellington Avenue at Wall Street in Winnipeg. He was in Thompson on business the day his plane disappeared on Dec. 7, 1971 for what was to be an in-and-out single day trip, but it is not certain now exactly what the business was. It may or may not have been related to proposed work for the School District of Mystery Lake since school construction projects were one of his areas of expertise.

Macdonald, who graduated from the University of Manitoba with his civil engineering degree in 1950, often worked with architectural firms, including his brother’s. Other than working for a year in Saskatoon, he spent his entire career living and working in Winnipeg. Macdonald, who was born on March 20, 1925, trained as a pilot when he was 19 and joined the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) shortly before the Second World War ended in 1945 and before he could be shipped overseas into the theatre of combat operations. His son, Bill Macdonald, was 15 when his dad disappeared in 1971 and is a Winnipeg teacher and freelance journalist, who in 1998 wrote The True Intrepid: Sir William Stephenson and the Unknown Agents, telling the story of the British Security Coordination (BSC) spymaster – codename Intrepid – set up by British Secret Intelligence Service (MI6). Ian Fleming, the English naval intelligence officer and author, best known for his James Bond series of spy novels, once said of his friend Stephenson, a Winnipeg native: “James Bond is a highly romanticized version of a true spy. The real thing is … William Stephenson.”

Macdonald had filed a 3½-hour flight plan to fly Visual Flight Rules (VFR) via Grand Rapids to Winnipeg that Tuesday. It was around -30 C at the time of takeoff on Dec. 7, 1971 and the winds were light from the west at five km/h, according to Environment Canada weather records, said Dale Marciski, a recently retired meteorologist with the Meteorological Service of Canada in Winnipeg. Macdonald was reportedly wearing a brown suit jacket when he took off from Thompson and it was unknown whether the plane was carrying winter survival clothing and gear.

While there was some ice fog, Marciski said, the sky was mainly clear and visibility was good at 24 kilometres. Transport Canada’s VFRs for night flying generally call for aircraft flying in uncontrolled airspace to be at least 1,000 feet above ground with a minimum of three miles visibility and the plane’s distance from cloud to be at least 2,000 feet horizontally and 500 feet vertically. Transport Canada investigated the disappearance of Macdonald’s flight in 1971 because the Transportation Safety Board (TSB) had yet to be created.

Macdonald’s disappearance triggered an intensive air search that at its peak in the days immediately after the aviator went missing involved more than 100 personnel covering almost 20,000 miles in nine search and rescue planes from Canadian Armed Forces bases in Edmonton and Winnipeg, including a Lockheed T-33 T-bird jet trainer and two de Havilland short takeoff and landing CC-138 Twin Otters, two RCMP planes and 11 civilian aircraft.

The search for Macdonald and his Mooney Mark M20D began only hours after his disappearance, on the Tuesday night. The Lockheed T-33 T-bird jet trainer flew the missing aircraft’s intended flight line from Winnipeg to Thompson and back to Winnipeg. The T-33 carried highly sophisticated electronic equipment and flew Macdonald’s flight plan both ways at extremely high altitude hoping to pick up signals from the Mooney Mark M20D’s emergency radio frequency, or the crash position indicator, a radio beacon designed to be ejected from an aircraft if it crashes to help ensure it survives the crash and any post-crash fire or sinking, allowing it to broadcast a homing signal to search and rescue aircraft, which was believed be carried by Macdonald on the Mooney Mark M20D.

The next morning – Dec. 8, 1971 – search and rescue aircraft re-flew the “track” in a visual search both ways, assisted by electronic listening devices, to no avail.

The area between Winnipeg and Thompson on both sides of the intended flight pattern was then zoned off and aircraft were assigned to particular zones and then flew the zones from east to west at one mile intervals until the entire area was over flown – first at higher altitudes and then again at lower altitudes.

Every private or commercial pilot flying the area assisted the organized search. Thompson Airport’s central tower was issuing a missing plane report at the end of every transmission, asking pilots in the area to keep a visual watch for Macdonald’s aircraft, and to listen for transmissions on the emergency band on their radios.

A second search for Macdonald and his Mooney Mark M20D single-engine prop aircraft was commenced almost six months later in May 1972, after spring had arrived in Northern Manitoba and all the snow had melted. Nothing turned up.

Who then was D.B. Cooper? The question still preoccupies old-time FBI agents and mystery aficionados alike.

There were nine frequently discussed suspects – all Americans, as far as I am aware – over the years: Kenneth Christiansen, Lynn Doyle Cooper, Richard Floyd McCoy, Jr., Duane Weber, Jack Coffelt, William Gossett, Barbara (formerly Bobby) Dayton, John List and Ted Mayfield. Most had military combat experience. All the suspects are in fact dead now, with the exception of Mayfield, who denies being D.B. Cooper.

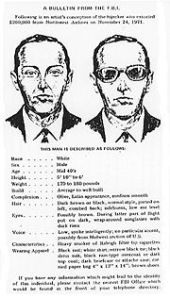

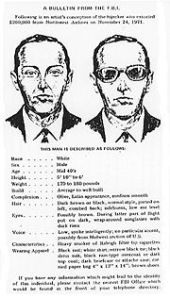

On Wednesday, Nov. 24, 1971 – 43 years ago today and the day before American Thanksgiving that year – someone using the alias Dan Cooper, which quickly got mistakenly turned into D.B. Cooper, committed the most audacious act of air piracy in U.S. history with the mid-afternoon skyjacking of Northwest Orient Airlines Flight 305, flying over the Pacific Northwest, en route from Portland, Oregon to Seattle, Washington with 36 passengers and six crew members aboard.

He paid $20 cash for his airline ticket in Portland. Once on board, Cooper passed a note to flight attendant Florence Schaffner demanding $200,000 ransom in unmarked $20 bills and two back parachutes and two front parachutes. Initially, Schaffner dropped the note unopened into her purse, until Cooper leaned toward her and whispered, “Miss, you’d better look at that note. I have a bomb.”

The day-before-Thanksgiving flight landed in Seattle, where passengers were exchanged for parachutes, including possibly an NB-8 rig with a C-9 canopy, known as a “double-shot” pinch-and-pull system that in 1971 would have allowed jumpers to disengage quickly from their chutes after they landed so that the wind did not drag them, and the cash, all in $20 bills, as he had demanded, although not unmarked it would turn out.

The plane took off again with only Cooper and the crew aboard about half an hour later. Cooper told the pilot to fly a low-speed, low-altitude flight path at about 120 mph, close to the minimum before the plane would go into a stall, at a maximum 10,000 feet, to aid in his jump. To ensure a minimum speed he specified that the landing gear remain down, in the takeoff and landing position, and the wing flaps be lowered 15 degrees. To ensure a low altitude he ordered that the cabin remain unpressurized.

He bailed out into the rainy night through the plane’s rear stairway, which he lowered himself, somewhere near the Washington-Oregon boundary in Washington State, probably near Ariel in Cowlitz County, or possibly around Washougal or Camas in Clark County.

In February 1980, eight-year-old Brian Ingram, vacationing with his family on the Columbia River about 20 miles southwest of Ariel, uncovered three packets of $5,800 of the ransom cash, disintegrated but still bundled in rubber bands, as he raked the sandy riverbank beachfront at an area known as Tina’s Bar to build a campfire on the Columbia River about 20 miles southwest of Ariel.

So why do we remember D.B. Cooper some 43 years later? Was the 1971 jump from 10,000 feet into the sub-freezing temperatures and bitter wind-chills during freefall even survivable?

Geoffrey Gray, a contributing editor at New York magazine and the author of Skyjack: The Hunt for D. B. Cooper, suggested in a New York Times article on Aug. 6, 2011 that it’s the “not-knowing” that makes Cooper so compelling for us. “In an age when we receive answers to our questions so quickly – now as fast as a midsentence trip to Wikipedia – the fact that we still don’t know who Cooper is feels somehow unfair,” Gray argues.

“Even some lawmen who scoured the woods for Cooper four decades ago suggested they hoped they would come up short.

“If he took the trouble to plan this thing out so thoroughly, well, good luck to him,” one local sheriff said.

But no trace of Cooper or Macdonald have ever been found.

While some 675,000 Americans died over three years between January 1918 and December 1920 during the three waves of the Spanish Flu pandemic, the country’s population was 103.2 million. Today, the population of the United States is more than 331 million. The world population in 1918 was about 1.8 billion, compared to about 7.8 billion people today.

While some 675,000 Americans died over three years between January 1918 and December 1920 during the three waves of the Spanish Flu pandemic, the country’s population was 103.2 million. Today, the population of the United States is more than 331 million. The world population in 1918 was about 1.8 billion, compared to about 7.8 billion people today.

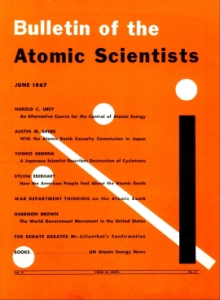

The rolling real time daily death count on the online COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU) in Baltimore functions as our equivalent of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists’ “Doomsday Clock,” circa 1947, and the clock itself, set at 100 seconds before midnight last Jan. 27, is being profoundly influenced by COVID-19.

The rolling real time daily death count on the online COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU) in Baltimore functions as our equivalent of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists’ “Doomsday Clock,” circa 1947, and the clock itself, set at 100 seconds before midnight last Jan. 27, is being profoundly influenced by COVID-19.