People took to the streets around the world to celebrate en masse the end of the first truly global war. Any cursory search of a newspaper or library archive will produce an abundance of black-and-white scenes of jubilation when the First World War ended Nov. 18, 1918 – 105 years ago this coming Saturday.

People took to the streets around the world to celebrate en masse the end of the first truly global war. Any cursory search of a newspaper or library archive will produce an abundance of black-and-white scenes of jubilation when the First World War ended Nov. 18, 1918 – 105 years ago this coming Saturday.

Over by Christmas. But not.

“Late on Christmas Eve 1914,” writes Amanda Mason, senior curator-historian with the Imperial War Museum in London, “men of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) heard Germans troops in the trenches opposite them singing carols and patriotic songs and saw lanterns and small fir trees along their trenches. Messages began to be shouted between the trenches. The following day, British and German soldiers met in no man’s land and exchanged gifts, took photographs and some played impromptu games of football. They also buried casualties and repaired trenches and dugouts.” Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who created Sherlock Holmes, later described it as an “amazing spectacle.” Stille Nacht, Heilige Nacht and Joyeux Noël and soccer matches in no man’s land with the impromptu Christmas Truce of 1914 in the trenches of the Western Front. But still not over.

Trench warfare. Mustard gas. Shellshock. The best-and-brightest young men and women of a generation from both the Allies, or the Entente Powers, and the Central Powers, senselessly slaughtered. A war that was supposed to be four months long but went on for more than four years. There were 20 million deaths and 21 million wounded in the First World War. The total number of deaths includes 9.7 million military personnel and about 10 million civilians.

The First World War stands as the real demarcation line between the 19th and 20th centuries and an older world and the modern era. In 1983, Ohio State University historian Stephen Kern wrote The Culture of Time and Space, 1880-1918, a book that talked about the sweeping changes in technology and culture that reshaped life, including the theory of relativity and introduction of Sir Sanford Fleming’s worldwide standard time. All of these things created new ways of understanding and experiencing time and space during that almost 40-year period ending with the end of the First World War. Kern’s argument is that in the modern preoccupation with speed, especially with the fast and impersonal telegraph, international diplomacy broke down in July 1914. Yet there were still vestiges of that older world of shared values and decency – even among enemies – and even in the barbarism of trench warfare in the early months of the First World War.

What came to be known as the “Great War” began on July 28, 1914 with Austria-Hungary’s declaration of war on Serbia, igniting the first truly global war. Honduras wouldn’t declare war on Germany until July 19, 1918, while Romania, which declared war with Austria-Hungary on Aug. 27, 1916, exited the war with the Treaty of Bucharest on May 7, 1918, only to re-enter it on Nov. 10, 1918, declaring war on Germany, a day before the First World War ended on what would come to be known as Armistice Day a year later in 1919.

Pte. George Lawrence Price, 25, of Falmouth Nova Scotia, is believed to be the last Canadian soldier to die in battle during the First World War. He served with the Canadian Infantry (Saskatchewan Regiment) and had enlisted in Regina on Oct. 15, 1917. Pte. Price was shot by a German sniper in Mons, Belgium at 10:58 a.m. on Nov. 11, 1918 – just two minutes before the Armistice went into effect at 11 a.m. Paris Time and very close to the spot the first Allied casualty of the First World War, British Pte. John Parr, of the Middlesex Regiment, had been killed on Aug. 21, 1914. Both Parr and Price are buried at nearby St. Symphorien Military Cemetery.

The last four Allied First World War veterans died just over a decade ago. Florence Green, of King’s Lynn, the last surviving veteran, who served briefly as a mess steward at air bases in Norfolk, England in 1918, died at the age of 110 on Feb. 4, 2012. Claude Stanley Choules, who lived in Perth, Australia and was the last known combat veteran of the First World War, having been posted to the battleship HMS Revenge in 1917, where he witnessed the surrender of the German Fleet near Firth of Forth in Scotland in 1918, emigrated from Britain to Australia in 1926 and retired from the navy in 1956, died at the age of 110 on May 5, 2011. Frank Woodruff Buckles, of Gap View Farm, near Charles Town, West Virginia, lied about his age to enlist in the United States Army in 1917, and became the last known U.S. veteran of the First World War when he died on Feb. 27, 2011 at the age of 110. With the death of Buckles, the last American “doughboy,” the United States government on March 12, 2011 issued the formal announcement of “the passing of a generation,” something it hadn’t done since Sept. 10, 1992 when Nathan E. Cook, the last known U.S. veteran of the Spanish-American War of 1898, died. John Henry Foster Babcock, Canada’s last surviving veteran of the First World War, died in Spokane, Washington on Feb. 18, 2010 at the age of 109.

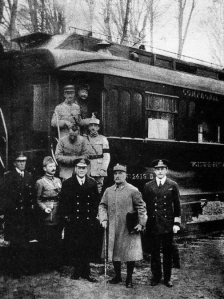

Now known as Remembrance Day, which commemorates Canadians who died in service to Canada from the South African War or, as it is also known, the Boer War, between 1899 and 1902, to current missions, Armistice Day, as it was known in Canada until 1931, the day the actual armistice was signed in a railway car in the Allied war zone in France’s Compiègne Forest, was anything but a solemn occasion on Nov. 11, 1918. Soldiers and civilians dancing in the streets and even riots were the order of the day. After four years of war, it would be surprising if it had been otherwise. Here in Canada, from 1923 to 1931, Armistice Day was held on the Monday of the week in which Nov. 11 fell. Thanksgiving was also celebrated on the same day. The name Armistice Day was changed to Remembrance Day in 1931 and fixed as Nov. 11. The South African War marked Canada’s first official dispatch of troops to an overseas war. Of the more than 7,000 Canadians who served in South Africa, 267 were killed.

The silence and solemnity that now marks Remembrance Day was proposed by an Australian journalist by the name of Edward Honey, who was working in London’s Fleet Street in 1919.

Honey, who had served briefly in the British Army during the First World War, before receiving a medical discharge, wrote a letter to the editor of The Evening News in London on May 8, 1919 under the pen name Warren Foster suggesting an appropriate commemoration for the first anniversary of the Armistice would be “five silent minutes of national remembrance.” Honey had been angered by the way in which people had celebrated with dancing in the streets on the day of the Armistice.

On the first anniversary of the Armistice in 1919 two minutes’ silence was instituted as part of the main commemorative ceremony at the new Cenotaph in London. King George V personally requested all the people of the British Empire to suspend normal activities for two minutes on the hour of the armistice “which stayed the worldwide carnage of the four preceding years and marked the victory of Right and Freedom.”

You can also follow me on X (formerly Twitter) at: https://twitter.com/jwbarker22