Ted and Mary Goossen, U-Haul truck packed, decamped from Thompson, Manitoba yesterday to begin their new and richly-deserved retirement in Saskatoon closer to their children and grandchildren.

Fortuitously, their home on Riverside Drive, after many months on the market, sold over their last weekend here, with the realtor informing them just before Ted arrived at Christian Centre Fellowship Sunday morning to preach his last sermon as pastor there for the last decade.

Ted’s younger brother, Gareth Goossen, who is also a pastor and lives in Breslau in southwestern Ontario, aptly observed in a Facebook posting: “Awesome! Praise the Lord! I continually am amazed at how Jesus answers our prayers at the last possible moment!!!”

I first got to know Ted in 2008, a few months after I arrived in Thompson to edit the Thompson Citizen and Nickel Belt News. We were kicking around the idea of adding some fresh columns and columnists and one of the ideas that was floated during the summer of 2008 was to have some sort of religion column.

Some of the initial discussion I had, mainly via e-mail, was with Rev. Leslie-Elizabeth King, who retired in May 2014 as minister of the Lutheran-United Church of Thompson on Caribou Drive, but at the time was pastor of St. John’s United Church, before the neighbouring congregations of Advent Lutheran and St. John’s United formally joined together in 2013, after starting a dialogue about their respective futures in 2008.

The old Advent Lutheran Church building was demolished last fall and is the future site of what will be the second Thompson Gas Bar Co-operative store in town.

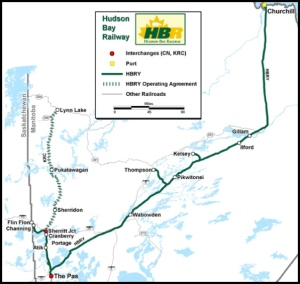

King had also pastored St. Simon’s Anglican Church in Lynn Lake, a shared ecumenical ministry of the United and Anglican churches, having travelled to St. Simon six times a year since 1998 to administer the sacraments, so she had some broad and candid insights into how religion was done in Northern Manitoba.

Bea Shantz was also originally involved in some of those preliminary discussions I had in the summer and fall of 2008. Shantz was a member of Thompson United Mennonite Church until it closed in July 2006. One of the first churches in Thompson, the Thompson United Mennonite Church formed in 1961. The congregation called its first pastor, John Harder, and built its house of worship at 365 Thompson Dr. in 1963. The Thompson Boys and Girls Club eventually bought the former church.

After it closed, Shantz went to St. John’s United Church and the Lutheran-United Church of Thompson, with the merger of the two churches.

Shantz, originally from southwestern Ontario, lived in Thompson for more than 30 years before she, and her husband, Dale, moved to Winnipeg in June. Shantz was well-known for being an active volunteer in numerous areas, but especially in more recent years with Thompson’s Communities in Bloom committee, as well as the annual Ten Thousand Villages sale of fair trade products from developing countries held every November. She received the 2013 Volunteer of the Year award from the City of Thompson and YWCA of Thompson Women of Distinction award last April.

But in December 2008, it would be Pastor Ted Goossen, who was still pretty much unknown to me, whose name would surface as the co-ordinator of what was to be a new “Spiritual Thoughts” column, which with the exception of one hiatus of a few months after running for several years, has run and continues to run in the Nickel Belt News for going on seven years now.

While the column belongs to the paper, the co-ordination of getting authors to write for it on an almost weekly basis, was delegated from the beginning, under my tenure anyway, to the Thompson Christian Council, and from 2008 until at least my departure in 2014, and from what I’ve been told, beyond, to Pastor Ted Goossen, whose Christian Centre Fellowship is a member of the council.

While most of the columnists in the rotation have overwhelmingly been local clergy who are members of the council over the years, not all have. Pastors whose churches are not members of the Thompson Christian Council, lay people, and on occasion non-Christian perspectives and writers, have also appeared in the column space from time-to-time, a plurality of views I insisted on. For their part, in my experience the Thompson Christian Council always graciously respected the fact while the “Spiritual Thoughts” column was a useful vehicle for evangelizing, at the end of the day it was not theirs, and in some cases not reflective of their views collectively or individually.

More than once, as Ted tried to put together six-month writing rosters for the “Spiritual Thoughts” column in those early days, I would quip to him, often in an e-mail, that organizing such a roster must be something like “herding cats.” While Sunday (or Saturday for Seventh-day Adventists) preaching may the most visible part of what most pastors do, there’s also plenty to do on the other days of the week, such as visiting the sick and burying the dead, and comforting those left behind, or marriage preparation or marriage counseling. Lots to do in other words beside a writing a free column for a newspaper, as heretical as that notion may seem in some journalism circles.

It was about three months after the “Spiritual Thoughts” column started that I had my first social invitation from Ted and Mary to visit Christian Centre Fellowship for an event. Every February or March, the church holds a family enrichment weekend that usually kicks off with a banquet and featured speaker on the Friday night (occasionally the banquet has been on Saturday) and wraps up with a movie night Sunday evening. In February 2009, Jeanette and me found ourselves seated at a table with Tricia Kell, the featured speaker for the weekend, Majors Grayling and Jacqueline Crites from the Thompson Corps of the Salvation Army, a couple that I knew about as well as Ted at that time, and Ted and Mary (when Mary wasn’t working in back in the kitchen.)

Kell is the author of two books, one of which is Chain of Miracles, the 2004 story of how she said the “power and love of God can change a chain of tragedies into a chain of miraculous victories.”

The book described how “God walked her through the abusive relationship and tragic death of her first husband to the accidents that left two of her children both physically and mentally challenged – to another horrifying incident that nearly killed her current husband.”

Kell was born in Halifax and raised as a Roman Catholic. A self-described “air force brat,” she lived in both Europe and Canada growing up. Later, she said, she “developed, owned and managed a successful clothing design company along with other companies.”

She described in Chain of Miracles how her first husband, Jeffrey, with a gun in the vehicle and their three-month-old son, J.J., threw them from a car into a ditch between Ponton and Thompson.

Kell, and her current husband, Gord, live in Winnipeg with their three adult children.

Her second book, Attitude Determines Altitude, was a humorous book, she said, “still based on my everyday life but tells how I beat my fear of flying.” It was published in 2008.

The following year we received a return invitation to share dinner with Paul Boge, the Winnipeg engineer-author-filmmaker.

Boge is an award-winning author who has written The Urban Saint: The Harry Lehotsky Story; Father to the Fatherless: The Charles Mulli Story; Hope for the Hopeless: The Charles Mulli Mission; and most recently, The Biggest Family in the World, chronicling the life of Charles Mulli in an illustrated children’s book published last December.

He has also written two novels in a potential trilogy, The Chicago Healer in 2004, and The Cities of Fortune in 2006.

In 2010, Boge talked about his then recently published book, The Urban Saint: The Harry Lehotsky Story, which explored the life of old west end Winnipeg inner city pastor Harry Lehotsky, who died of pancreatic cancer in 2006 at age 49.

Boge won Word Guild’s best new Canadian author award in 2003 for his first book, The Chicago Healer, published the following year.

In addition to being an author, Boge, is a consulting mining engineer and capital project manager with the family firm Boge & Boge Consulting Engineers in Winnipeg, and no stranger to Thompson. He lived and worked here for nine months in 2003, five months in 2005 and for another 10 months in 2007, while working on three separate surface projects for Vale, and doing much of his writing in his apartment at night.

Boge is also behind FireGate Films, an independent Winnipeg company that made the 2006 feature-length movie Among Thieves, with Boge writing, directing and producing the film, which explores the possibility the end is in sight for the United States dollar as the world’s reserve currency, as Gulf Arab countries including Saudi Arabia, Abu Dhabi, Kuwait and Qatar have contemplated ending dollar dealings for oil and moving to a basket of currencies including the euro and Chinese yuan or renminbi. The last Middle East oil producer to sell its oil in euros rather than U.S. dollars was Saddam Hussein’s Iraq in 1990.

Boge is also the co-ordinator for the annual Winnipeg Real to Reel Film Festival at North Kildonan Mennonite Brethren Church in mid-February. He is a member of the church.

Five years later, Boge returned as the keynote speaker again this year for the Feb. 27 to March 1 weekend, sharing about his work and how he integrates his faith into his work environment. We’ve kept in touch by e-mail here and there over the last five years and we saw him briefly in Winnipeg in February 2012 at the Real to Reel Film Festival.

Paul’s a great guy and fun to hang around with. So this year, in a bit of a break from tradition, where we had only attended the kick-off banquet or sometimes the Sunday chili dinner and movie night, Jeanette and me ventured out to Nick DiVirgilio’s NC Crossroad Lanes upstairs at his North Centre Mall on Station Road for some Saturday afternoon five-pin bowling. We wound up on a team with Paul. Never let it be said Christians can’t be competitive.

Besides the annual family enrichment weekend, over the last seven years, I’ve dropped by the odd Sunday morning to check out a worship service, usually with Jeanette, but sometimes on my own when she’s been away at International Music Camp in Dunedin, North Dakota. And over this past year I attended every other Saturday at 9 a.m. for their men’s fellowship breakfast, which wrapped up for the season June 13.

How I wound up going to the breakfasts was through a typical Ted invitation. Last Oct. 17, at 7:41 p.m. on a Friday evening I received an e-mail Ted: “We’re having men’s breakfast tomorrow 9 am @ Christian centre.

“You’re welcome to join us.

“Ted.”

Truth be told, the invitation was Mary’s idea. For these mainly, but not exclusively, Mennonite Brethren to invite a third-degree member of Knights of Columbus Thompson Council #5961 from St. Lawrence Roman Catholic Church parish here to break bread with them struck me somewhat irreverently perhaps as in keeping with Jesus telling Zacchaeus the tax collector he was coming over for dinner. It also struck me as the kind of invitation my current supreme pontiff, Pope Francis, wouldn’t hesitate to accept. Before I moved to Manitoba in 2007, I knew next to nothing about Mennonites. What little I knew living and working mainly in Southern Ontario was shaped by images of the Old Order Mennonites of St. Jacobs, Ontario. Or was that the Old Order Amish of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania? Who knew? While I may not have sorted it all out or ever will, I’m pretty sure the Mennonite Brethren I had breakfast with were not Old Order, although I have encountered Old Order-like Mennonites here in Thompson (I once asked a group caroling at Christmas when I was editor of the Thompson Citizen if they would mind me taking their photograph in one of those “duh-what-was-I-thinking” moments. Their leader graciously told me while his salvation wasn’t going to depend on whether or not I took his picture, out of deference to their religious beliefs, he’d rather I didn’t.)

Now Protestant evangelicals are sola scriptura or the “People of the Book,” while Catholic theology relies on the rule of faith-based scripture, plus apostolic tradition, as manifested in the teaching authority of the magisterium of the Catholic Church. Catholics, outside of the seminary or Catholic scholarship, at the rank-and-file lay level in the pews, are generally not catechesized to know the Bible as well as Protestants do. That’s a plain and simple fact. So I appreciated the indulgence of my Protestant brothers during biblical discussions. I still chuckle when I recall the Saturday morning I was attempting to illustrate some point by referring to the Apostle Paul before the Areopagus, where some of the assembled said, “We shall hear you again concerning this,” but I could not quite place where it was in the Bible, and pilot Reg Willems, since decamped to Flin Flon, sitting beside me at the table, said gently, “That would be in Acts, John.”

I learned a lot through those discussions with Ted and Reg, Lloyd Penner, Jason Winship, Dustin Winker, Trevor Giesbrecht, Barry Little, Keith Hyde, Gord Unger, Ken Giesbrecht, Keith Derksen, Claude Pratte, Cohle Bergen, Peter Gosnell, Bill Lennox, Jim Cohan, Wei Wei, Adam Morin and Nick Yoner (with Keith, Gord and Dustin usually doing the cooking). Thanks, guys.

I also learned something about accountability in friendship through Ted these past seven years, as he wouldn’t hesitate to call you on something, if need be.

Two examples from our “Spiritual Thoughts” column collaborative efforts come to mind. The first occurred near the beginning of our work together in 2009, the other near the end in 2014.

In the first case, Jordan McLellan, who was the assistant pastor at the Thompson Pentecostal Assembly, focusing on youth ministry from mid-2007 until he left for Saskatoon to take a position at Lawson Heights Pentecostal Assembly in early 2010, had missed a couple of his submissions for the column without explanation.

I recall fuming to Ted in a telephone call that if McLellan missed a third contribution in such a manner, I was going to “irrevocably” drop him from the column rotation. Perhaps it was the word irrevocably that did it, but Ted didn’t miss a beat with his response, replying that he was glad then that I wasn’t the “good Lord.” Point taken. And never forgotten.

Just over a year ago, young Richard Sheppard, group leader of the Thompson Seventh-day Adventist Congregation, asked to join the “Spiritual Thoughts” rotation. At the time, the local Seventh-day Adventists weren’t part of the Thompson Christian Council (they were admitted by a unanimous vote this past spring) but that wasn’t in itself a bar to Sheppard writing, nor was Seventh-Day Adventist theology. By virtue of their valid baptism, and their belief in Christ’s divinity and in the doctrine of the Trinity, Seventh-day Adventists are both ontologically and theologically Christians. The real problem was perceived to be Sheppard himself, who is off this fall to a Seventh-day Adventist post-secondary school in Lacombe, Alberta.

Richard is a controversialist, by design or evolution, I’m not sure which. He’s zealous. He’s in-your-face. In short, he’s everything management of the Nickel Belt News did not want to see in the pages of the paper in what had been a pretty safe and non-controversial column space.

Management was adamant. That is until Ted outflanked us from the left – for probably the first and only time in his life.

When I sent Ted an e-mail relaying the news that Sheppard wouldn’t be joining the roster, he replied with his own hard-hitting e-mail pointing out that several years earlier when we had briefly run a columnist in that space whose views were anathema to most of the clergy on the council, they had swallowed hard and realized newspapers are supposed to be about free speech.

What happened to that notion, Ted wondered?

Essentially, he accused of us pre-publication censorship and betraying our free speech principles.

What Richard needed was a good editor to work with him and perhaps tone him down a bit in places, not to spike the column entirely, Ted argued.

I shared Ted’s response with my boss, and observed how professionally embarrassing it was to be lectured on free speech and the role of a newspaper by an evangelical pastor who at that moment had truth very much on his side, and was making us look like moral cowards and far more conservative than any views he held.

Ted’s argument prevailed, and Richard Sheppard’s first “Spiritual Thoughts” column, critiquing the popular Christian movie Heaven is for Real, which in Richard’s words was “a spellbinding tale about a young toddler in a clerical family who ostensibly dies on an operating table, visits heaven and comes back with mystifying facts from ‘beyond the grave’ that his own father finds hard not to accept,” ran on June 20, 2014 in the Nickel Belt News, albeit toned down a tad from the original submission, where (and I’m paraphrasing only slightly here, I believe, from memory) Richard suggested the movie was an exercise in necromancy, not a word we saw in a lot of column submissions, and which was excised from what appeared in print – but the entire column did not need to be axed, which was part of Ted’s point.

To my knowledge the particular column generated no complaints. And last I counted, Richard had gone onto write at least five more “Spiritual Thoughts” columns for the paper.

I ran into Richard in person in early April and told him he had Ted to thank for making it into the column rotation. He seemed pleasantly surprised. Nice kid, really.

Safe travels, Ted. Manitoba’s loss is Saskatchewan’s gain.

You can also follow me on Twitter at: https://twitter.com/jwbarker22

55.737404

-97.862943