Think of today as “D.B. Cooper Wednesday,” if you will. Because on the Wednesday and day before American Thanksgiving 52 years ago, D.B. Cooper, with his audacious skyjacking, jumped into history on Nov. 24, 1971.

“Have we checked the spare parachute packing card slot? What about the rip cords? Wait, the parachute, was it a 24-foot canopy or a 26-foot canopy? Is there DNA on the tie clip? And, my goodness, how did the money end up at Tena Bar?” asked David Gutman, a Seattle Times staff reporter in a story Nov. 18.

“The questions linger, they spiral, becoming ever more arcane,” he noted.

“If you’re not versed, if you don’t know about the copycats and the diatoms and the titanium particles, it all sounds like Greek.

“But for those who’ve been hooked, captivated, enthralled, the legend of D.B. Cooper does not fade. It is a subculture.”

The number one song that day on Nov. 24, 1971 on AM transistor radios across the country was Isaac Hayes’ Theme from Shaft, the movie released four months earlier, starring Richard Roundtree as detective John Shaft.

Meanwhile, the chill surface temperature at ground level in Ariel, Washington, situated north of the Lewis River and on the northwest bank of Lake Merwin in Cowlitz County, not far north of the Oregon State line, was 20°F at 8:12 p.m. Pacific Standard Time (PST).

Around this time every November, searches on my blog spike upwards for all things D.B. Cooper related. It is, I noted on Facebook, “the story that keeps on giving.” Remarkably, most years there is still publicity throughout the media, especially in the U.S. Pacific Northwest, focusing on a newly discovered suspect, albeit they are all very old or dead now.

I came kind of late to writing about the D.B. Cooper case, first penning a column on it 12 years ago for the Thompson Citizen back on Nov. 23, 2011. I must have made up for lost time because less than five years later, “Fox Mulder will continue to investigate regardless. And possibly John W. Barker,” Ian Graham, then editor of the Thompson Citizen and Nickel Belt News, wrote on Facebook July 12, 2016.

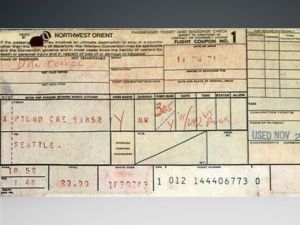

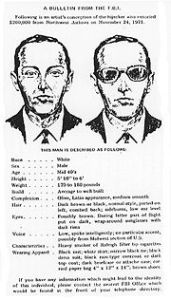

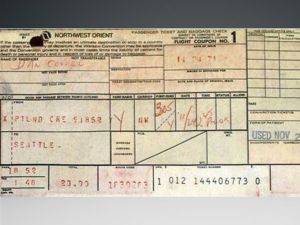

On Wednesday, Nov. 24, 1971 – the day before American Thanksgiving that year – someone using the alias Dan Cooper, which quickly got mistakenly turned into D.B. Cooper, committed the most audacious act of air piracy in U.S. history with the mid-afternoon skyjacking of Northwest Orient Airlines Flight 305, a Boeing 727 jetliner flying over the Pacific Northwest, en route from Portland, Oregon to Seattle, Washington with 36 passengers and six crew members aboard.

He paid $20 cash, which included tax, for his airline ticket in Portland. Once on board, Cooper, a nondescript man possibly with a slight Midwestern accent, ordered a bourbon-and-soda, before passing a note to flight attendant Florence Schaffner demanding $200,000 ransom in unmarked $20 bills and two back parachutes and two front parachutes. ‘I HAVE A BOMB IN MY BRIEFCASE. I WILL USE IT IF NECESSARY. I WANT YOU TO SIT NEXT TO ME. YOU ARE BING (sic) HIJACKED.’ Initially, Schaffner dropped the note unopened into her purse, until Cooper leaned toward her and whispered, “Miss, you’d better look at that note. I have a bomb.” Cooper smoked eight Raleigh filter-tipped cigarettes on the plane, but there was no evidence to show if this was a regular habit of his.

The day-before-Thanksgiving flight landed at Tacoma International Airport in Seattle, where passengers were exchanged for parachutes, including possibly an NB-8 rig with a C-9 canopy, known as a “double-shot” pinch-and-pull system that in 1971 would have allowed jumpers to disengage quickly from their chutes after they landed so that the wind did not drag them, and the cash, all in $20 bills, as he had demanded, although not unmarked it would turn out. The passengers were never aware of the threat onboard. A bank in Seattle was contacted and a bag of money, all $20 bills with recorded serial numbers, totaling $200,000, was delivered to the plane, which was refueled and cleared for takeoff. The bag of ransom money itself weighed 23 pounds.

The plane took off again, heading toward Mexico at the hijacker’s command, with only Cooper and the crew aboard about half an hour later. Cooper told the pilot to fly a low-speed, low-altitude flight path at about 120 mph, close to the minimum before the plane would go into a stall, at a maximum 10,000 feet, to aid in his jump. To ensure a minimum speed he specified that the landing gear remain down, in the takeoff and landing position, and the wing flaps be lowered 15 degrees. To ensure a low altitude he ordered that the cabin remain unpressurized.

He bailed out into the rainy night through the plane’s rear stairway, which he lowered himself, somewhere near the Washington-Oregon boundary in Washington State, probably near Ariel in Cowlitz County, or possibly around Washougal or Camas in Clark County.

Along with FBI, Washington and Oregon state police, and local law enforcement officials, about 1,000 army troops and helicopters were also used in the 1971 search for Cooper.

In 1978, a placard containing instructions for lowering the aft stairs of a 727 was found by a deer hunter east of Castle Rock in Cowlitz County, which was within the basic flight path of the plane Cooper jumped from, according to the FBI and news reports.

In February 1980, eight-year-old Brian Ingram, vacationing with his family on the Columbia River about 20 miles southwest of Ariel, uncovered three packets of $5,800 of the ransom cash, disintegrated but still bundled in rubber bands, as he raked the sandy riverbank beachfront at an area known as Tena Bar to build a campfire on the Columbia River about 20 miles southwest of Ariel.

This year’s suspect is Vince Petersen. When the hijacked plane landed in Reno, Nevada, a black necktie was found onboard. The JC Penney clip-on tie was later found to have had a number of Rare Earth Elements (REE) on its surface, including cerium and strontium sulfide, along with pure titanium particles, all found on it. The only place that used that metal at the time was a lab called Rem Cru Titanium Inc. in Midland, Pennsylvania. Petersen worked there in the 1960s. The titanium research lab consisted of eight men, a small group of engineers, who wore neckties in the lab.

Those elements were used at the time of Cooper’s hijacking by Boeing at its assembly plant in Everett, Washington, 29 miles north of Seattle, in the production of high-tech electronics such as radar screens for their Super Sonic Transport Plane.

By 1966, deciding that jumbo jets were the future, Boeing acquired Paine Field, an old wartime military base in Everett, and built what remained in 2015 the largest building by volume in the world. It was the assembly plant for the company’s new jumbo jet, the Boeing 747, and the workforce soon exceeded 20,000 at Everett alone.

The first 747 rolled out of the giant building in 1969. The plant is the size of 40 football fields. Boeing is among the largest global aircraft manufacturers; it is the second-largest defense contractor in the world based on 2015 revenue, and is the largest exporter in the United States by dollar value.

As the 1970s dawned, the airliner market was saturated and the United States was slipping into recession. Boeing laid off more than 25,000 workers in 1969 and another 41,000 in 1970. Then in 1971 the United States Senate cut funding for Boeing’s sleek new Supersonic Transport, known as the SST, and the company cut nearly 20,000 more jobs. The workforce hit a low of 56,300.

The so-called “Boeing Bust” had put 86,000 workers on the street in three years.

Did D.B. Cooper work as an engineer, project manager or contractor for Boeing near Seattle in 1971? Did he have white collar connections to the recently downsized Puget Sound aerospace industry of the time?

There have been a number of Cooper suspects and persons of interest over the years, some more frequently discussed than others: Kenneth Christiansen, Lynn Doyle Cooper, Richard Floyd McCoy, Jr., Duane Weber, Jack Coffelt, William Gossett, Barbara (formerly Bobby) Dayton, John List, Melvin Luther Wilson, and Ted Mayfield. Most had military combat experience. And one Canadian, a Winnipeger who disappeared in 1971, just days after Cooper’s skyjacking, on a return trip from Thompson, Manitoba, flying solo. James (Jim) Hugh Macdonald, 46, the owner of J.H. Macdonald & Associates Ltd., consulting structural engineers on Pembina Highway in Winnipeg, climbed into his Mooney Mark M20D single-engine prop aircraft, bearing the registration mark CF-ABT, and took off half an hour after sunset from the Thompson Airport in Northern Manitoba at 4:30 p.m. on Dec. 7, 1971 to make his return flight home and disappeared into the rapidly darkening sky to never be seen or heard from again. He was the sole occupant of the four-seater plane.

On Sept 21, 2013, while editing the Thompson Citizen and Nickel Belt News, I received a three-sentence e-mail from a reader out of the blue saying, “I just read your article on James Macdonald. I would never want to disrespect the deceased/missing, but he fits the description of Dan Cooper. The FBI suspects D.B. Cooper was from Canada.”

Claire Macdonald, his wife, told me in an interview in December 2012 that someone once wildly jokingly said to her, “Maybe he flew to Mexico.” She said her reply was: “How far can you go in that little plane in that winter weather?” But the close nexus in time between the two aviation disappearances in late 1971 and the fact both men were Caucasians in their mid-forties made at least some Cooper and Macdonald comparisons inevitable.

J.H. Macdonald & Associates Ltd. was a small firm with about seven employees. Jim Macdonald was the only professional engineer on staff and a few months after his disappearance, its business affairs were wound down.

One of Macdonald’s last projects as a consulting structural engineer was the construction of additional classroom space for special needs students at Prince Charles School on Wellington Avenue at Wall Street in Winnipeg. He was in Thompson on business the day his plane disappeared on Dec. 7, 1971 for what was to be an in-and-out single day trip, but it is not certain now exactly what the business was. It may or may not have been related to proposed work for the School District of Mystery Lake since school construction projects were one of his areas of expertise.

Macdonald, who graduated from the University of Manitoba with his civil engineering degree in 1950, often worked with architectural firms, including his brother’s. Other than working for a year in Saskatoon, he spent his entire career living and working in Winnipeg. Macdonald, who was born on March 20, 1925, trained as a pilot when he was 19 and joined the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) shortly before the Second World War ended in 1945 and before he could be shipped overseas into the theatre of combat operations. His son, Bill Macdonald, was 15 when his dad disappeared in 1971 and is a Winnipeg teacher and freelance journalist, who in 1998 wrote The True Intrepid: Sir William Stephenson and the Unknown Agents, telling the story of the British Security Coordination (BSC) spymaster – codename Intrepid – set up by British Secret Intelligence Service (MI6). Ian Fleming, the English naval intelligence officer and author, best known for his James Bond series of spy novels, once said of his friend Stephenson, a Winnipeg native: “James Bond is a highly romanticized version of a true spy. The real thing is … William Stephenson.”

Macdonald had filed a 3½-hour flight plan to fly Visual Flight Rules (VFR) via Grand Rapids to Winnipeg that Tuesday. It was around -30 C at the time of takeoff on Dec. 7, 1971 and the winds were light from the west at five km/h, according to Environment Canada weather records, said Dale Marciski, a retired meteorologist with the Meteorological Service of Canada in Winnipeg. Macdonald was reportedly wearing a brown suit jacket when he took off from Thompson and it was unknown whether the plane was carrying winter survival clothing and gear.

While there was some ice fog, Marciski said, the sky was mainly clear and visibility was good at 24 kilometres. Transport Canada’s VFRs for night flying generally call for aircraft flying in uncontrolled airspace to be at least 1,000 feet above ground with a minimum of three miles visibility and the plane’s distance from cloud to be at least 2,000 feet horizontally and 500 feet vertically. Transport Canada investigated the disappearance of Macdonald’s flight in 1971 because the Transportation Safety Board (TSB) had yet to be created.

Macdonald’s disappearance triggered an intensive air search that at its peak in the days immediately after the aviator went missing involved more than 100 personnel covering almost 20,000 miles in nine search and rescue planes from Canadian Armed Forces bases in Edmonton and Winnipeg, including a Lockheed T-33 T-bird jet trainer and two de Havilland short takeoff and landing CC-138 Twin Otters, two RCMP planes and 11 civilian aircraft.

The search for Macdonald and his Mooney Mark M20D began only hours after his disappearance, on the Tuesday night. The Lockheed T-33 T-bird jet trainer flew the missing aircraft’s intended flight line from Winnipeg to Thompson and back to Winnipeg. The T-33 carried highly sophisticated electronic equipment and flew Macdonald’s flight plan both ways at extremely high altitude hoping to pick up signals from the Mooney Mark M20D’s emergency radio frequency, or the crash position indicator, a radio beacon designed to be ejected from an aircraft if it crashes to help ensure it survives the crash and any post-crash fire or sinking, allowing it to broadcast a homing signal to search and rescue aircraft, which was believed be carried by Macdonald on the Mooney Mark M20D.

The next morning – Dec. 8, 1971 – search and rescue aircraft re-flew the “track” in a visual search both ways, assisted by electronic listening devices, to no avail.

The area between Winnipeg and Thompson on both sides of the intended flight pattern was then zoned off and aircraft were assigned to particular zones and then flew the zones from east to west at one mile intervals until the entire area was over flown – first at higher altitudes and then again at lower altitudes.

Every private or commercial pilot flying the area assisted the organized search. Thompson Airport’s central tower was issuing a missing plane report at the end of every transmission, asking pilots in the area to keep a visual watch for Macdonald’s aircraft, and to listen for transmissions on the emergency band on their radios.

A second search for Macdonald and his Mooney Mark M20D single-engine prop aircraft was commenced almost six months later in May 1972, after spring had arrived in Northern Manitoba and all the snow had melted. Nothing turned up.

Who then was D.B. Cooper? The question still preoccupies old-time FBI agents and mystery aficionados alike. There have been a number of other Cooper suspects and persons of interest over the years, some more frequently discussed than others, including:

John List, a Second World War and Korean War veteran exited his ho-hum existence as a failed New Jersey accountant by killing his family in 1971, murdering his wife, three teenage children, and 85-year-old mother in New Jersey 15 days before the Cooper hijacking. After the murders, List withdrew $200,000 from his mother’s bank account and disappeared. He wasn’t arrested until 18 years later after Fox-TV’s America’s Most Wanted featured the case in a May 21, 1989 segment, displaying a bust of what an older John List might look like. The network estimated that 22 million people saw it. One was a woman in a suburb of Richmond, Virginia, who thought the bust looked like a neighbor, Robert Clark, a churchgoing accountant who wore horn-rimmed glasses. List, alias Clark, was arrested, tried and convicted, dying in custody in March 2008 at the age of 82.

William Pratt Gossett was a Marine Corps, Army and Army Air Force veteran who saw action in Korea and Vietnam. His military experience included advanced jump training and wilderness survival. Gossett died Sept. 1, 2003 at age 73, retired to Depoe Bay on the Oregon coast.

Galen Cook, a Spokane, Washington lawyer who’s been researching the Cooper case for more than 20 years, says Gossett once showed his sons a key to a British Columbia safety deposit box in Vancouver, which, he claimed, contained the missing ransom money.

His son Greg lives in Ogden, Utah, where he said his father told him on his 21st birthday that he had hijacked the plane.

“He said that I could never tell anybody until after he died,” Greg Gossett said.

Kirk Gossett, another son, says his father also told the story several times.

“He had the type of temperament to do something like this,” Kirk Gossett said.

After a career in the military, the elder Gossett worked in the early 1970s in Utah as an Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC) instructor, the a college-based program for training commissioned officers of the United States Armed Forces, and also as a military law instructor at Weber State University in Ogden. He also worked as a radio talk show host in Salt Lake City, where he moderated discussions about the paranormal.

Late in his life, Gossett reportedly told his three sons that he committed the hijacking, but the FBI was never able to implicate Gossett, and could never place him in the Pacific Northwest at the time of the Cooper hijacking.

“There is not one link to the D.B. Cooper case other than the statements [Gossett] made to someone,” Seattle Field Office Special Agent Larry Carr told ABC News.

Kenneth Christensen had been a paratrooper whose first deployment came just after the Second World War. After he left the military, he worked as a mechanic and a flight purser for Northwest Orient Airlines, the carrier that Cooper targeted for his 1971 skyjacking. Christensen loved bourbon bought a modest house not long after the crime skyjacking of Flight 305.

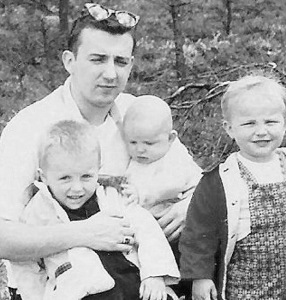

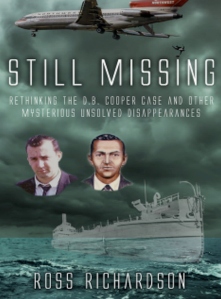

Now add to the Cooper suspect list Robert Richard Lepsy, a Glen’s Market grocery store manager and married father of four, three boys and a girl, who mysteriously vanished from Grayling, in the middle of northern Michigan, on Oct. 29, 1969. Lake Ann, Michigan author and shipwreck hunter, Ross Richardson, a Benzie County Sheriff’s Department special deputy, who volunteers as a librarian at the Almira Township Library, wrote a book published last year titled Still Missing, Rethinking the D.B. Cooper Case and other Mysterious Unsolved Disappearances.

On the day he disappeared, Dick Lepsy, 33, called his wife, Jackie, 31, around lunch time and told her he was going to go for a ride. Jackie Lepsy noted at least as early as 1986 in interviews that her husband’s company wood-paneled station wagon was found abandoned two days later at the Cherry Capital Airport in Traverse City, Michigan, approximately 50 miles northwest of Grayling, or about an hour away, with the doors unlocked, a half-pack of cigarettes were sitting on the dash, and the keys in the ignition. Also left behind was an empty bank account and a safe at Glen’s Market missing $2,000.

Despite the circumstances, investigating officers from the Grayling Police Department and Michigan State Police believed that Lepsy had disappeared “on his own accord,” so he was never officially listed as a missing person. As he wasn’t officially wanted for any crime and was believed to have disappeared voluntarily, little police effort was expended trying to locate Lepsy. Local Michigan media ignored Lepsy’s disappearance because it was considered more likely to be an embezzlement case than a missing persons case, and police kept it quiet.

But a little more than two years after Lepsy disappeared from Michigan, his then 13-year-old daughter, Lisa Lepsy, was watching the CBS Evening News, and saw the story of the Portland skyjacking.

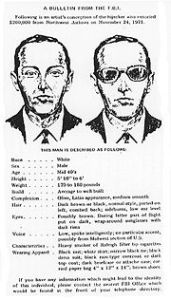

“We were all sitting on the couch watching Walter Cronkite,” she told WZZM13, the Tegna-owned ABC-TV affiliate in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Tegna is formerly Gannett Co., Inc. “When the composite sketch of D.B. Cooper came on the TV screen, everyone looked at each other and said, ‘That’s dad!’ We were stunned because the resemblance was unbelievable, and my brothers and I were all sure that was our dad.” The men were of similar height, about six feet tall, weighed about 180 pounds, and they both had brown hair and brown eyes. Lepsy, who had a high school education, was born in Chicago. Both Lepsy and Cooper wore black loafers and a skinny black ties. Cooper left a skinny black clip-on tie behind on the plane and, along with a tie clasp, while the skinny black tie was part of Lepsy’s mandatory managerial uniform at Glen’s Market in Michigan. DNA was extracted from Cooper’s tie finally 30 years after the skyjacking in 2001.

Lepsy’s family finally had his name added to the NamUs (National Missing and Unidentified Persons System) in 2011.

You can also follow me on X (formerly Twitter) at: https://twitter.com/jwbarker22