Provincial governments come and go in Manitoba, like elsewhere, but one of things that doesn’t change is my email reminder around this time every year: “Manitoba Municipal and Northern Relations reminds all Manitobans that daylight time will end in Manitoba early Sunday morning when clocks will be set back one hour,” the new NDP government’s Manitoba Municipal and Northern Relations department, presided over by Minister Ian Bushie, cheerily told me yesterday.

Provincial governments come and go in Manitoba, like elsewhere, but one of things that doesn’t change is my email reminder around this time every year: “Manitoba Municipal and Northern Relations reminds all Manitobans that daylight time will end in Manitoba early Sunday morning when clocks will be set back one hour,” the new NDP government’s Manitoba Municipal and Northern Relations department, presided over by Minister Ian Bushie, cheerily told me yesterday.

“Under the Official Time Act, daylight time ends on the first Sunday in November and resumes the second Sunday in March.

“The official time change back to central standard time will occur this year at 2 a.m., Sunday, Nov. 5 at which time clocks should be set back to 1 a.m.”

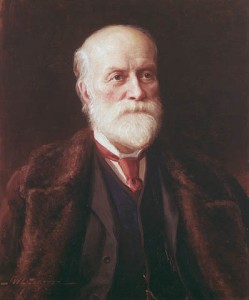

So at 2 a.m. in the morrow, we’re snoozing into Sunday’s Central Standard Time, (CST) in Manitoba, with our gratitude renewed for Scottish-born Canadian surveyor, engineer and inventor Sir Sandford Fleming, who we thank profusely for the extra hour of sleep.

While it has been gradually getting darker earlier in the evening since late June here in the Northern Hemisphere, the fact many of us, at least until tomorrow, can still travel home in waning daylight from work or school in the late afternoon in early November is in itself a credit to George Vernon Hudson, an English-born New Zealand amateur entomologist and astronomer who gave the world Daylight Saving Time (DST), a decade or so after Fleming’s development of Standard Time.

Hudson’s day (and sometimes night) job was as a clerk (eventually chief clerk) in the post office in the capital of Wellington on North Island. Hudson’s shift-work job gave him enough leisure time to collect insects, and led him to value after-work hours of daylight for that pursuit when he was working days. On Oct.15, 1895, spring in New Zealand, he presented a paper called “On Seasonal Time-adjustment in Countries South of Lat. 30°” to the Wellington Philosophical Society, proposing a two-hour daylight-saving shift, and after considerable interest was expressed in Christchurch on South Island, where 1,000 copies of his paper were printed in 1896, he followed up on Oct. 8, 1898 with a second paper, “On Seasonal Time,” also presented to the Wellington Philosophical Society in springtime, and which can be found in the Transactions and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New Zealand, housed at the National Library of New Zealand in Wellington.

It is Fleming, however, who deserves most of the credit for both the international dateline, and standard time zones, conveniently divided into hourly segments, dating back to October 1884 and the International Prime Meridian Conference attended by 25 nations in Washington, D.C. Before Fleming invented standard time, noon in Kingston, Ontario was 12 minutes later than noon in Montréal and 13 minutes before noon in Toronto. Noon local time was the time when the sun stood exactly overhead. As for the international date line, it is an imaginary line at the 180º line of longitude that runs from the South Pole to the North Pole separating two consecutive calendar days.

It was Hipparchus of Nicea, a Greek mathematician and astronomer, who around 150 BCE, proposed a global grid of longitude and latitude lines to measure position. It was a coordinate system for locating points on the surface of a sphere. The vertical axis measured “latitude,” and the horizontal axis “longitude.”

Immediately to the left of the international date line the date in the Eastern Hemisphere is always one day ahead of the date (or day) immediately to the right of the international date line in the Western Hemisphere. There is no regulatory body or agency that can say “yes” or “no” if a country wants to switch sides. The country simply lets the international community and mapmakers know. It is not a perfectly straight line, however, and has been moved slightly over the years to accommodate needs of varied countries in the Pacific Ocean. The Midway Islands are in Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) -11, and the Marshall Islands are in UTC+12. The two group of islands, on different sides of the international date line, share the same day and date for the last hour of the day. Samoa, which happens to sit in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, just 32 kilometres, or 20 miles, east of the international date line, went directly from Thursday – on Dec. 29, 2011 – to Saturday, Dec. 31 – without a Friday, Dec. 30. Talk about being anxious to party on New Year’s Eve!

Kiribati, north of Samoa and near the equator, south of Hawaii, previously straddled the dateline. The eastern part of Kiribati was a whole day and two hours behind the western part of the country where its capital is located and a time difference of 23 hours between neighbouring islands. There were nine islands on the eastern side of the international date line, and 20 per cent of the population. On Jan. 1, 1995 it added an eastward extension to its section of the dateline so all 33 of its islands would have the same date and all of Kiribati would be in the Eastern Hemisphere.

Since 1892, when Samoa had two Monday, July 4ths, it had been east of the international date line until Dec. 29, 2011, after switching sides to coincide its days better with trading partners in the United States and Europe. Now, Samoa does a lot more business with New Zealand, Australia, China and Pacific Rim countries such as Singapore, so it switched back to the western side of the international date line.

After missing a train in 1876 in Ireland because its printed schedule listed p.m. instead of a.m., Fleming proposed a single 24-hour clock for the entire world with 24 time zones and within each zone the clocks would indicate the same time, with a one-hour difference between adjoining zones. Usually, when one travels in an easterly direction, a different time zone is crossed every 15 degrees of longitude, which is equal to one hour in time. Usually. China, however, has just one time zone, which makes the time zone uncommonly wide. In the extreme western part of China the sun is at its highest point at 3 p.m. and in the extreme eastern part at 11 a.m. In 1912, the year after the collapse of the Qing Dynasty, the Republic of China had created five time zones in the country, ranging from five and a half to eight and a half hours past Greenwich Mean Time. But in 1949, as the Communist Party consolidated control of the country, Chairman Mao Zedong ordered that all of China use Beijing time.

Fleming was born on Jan. 7, 1827 in the town of Kirkcaldy in the lieutenancy area of Fife on the east coast of Scotland. He emigrated to Canada in 1845, settling in Peterborough in southeastern Ontario.

This year, as we shift back to Standard Time from Daylight Saving Time at 2 a.m. tomorrow, which means an extra hour of slumber for many, but also causes me to ponder the potential complications of moving the clock back an hour and repeating the hour from 1 a.m. to 2 a.m. What happens when the clock jumps backward at 2 a.m. again to 1 a.m. for the second time that night and then repeats the hour? Would you have official log chronologies showing 1:13 a.m., 1:37 a.m., 1:56 a.m., 1:03 a.m. and 1:12 a.m. with the later two actually coming after the first three because they came after the clock fell back an hour? How would you distinguish which came first if need be, if someone needed to inspect the log months later (add the annotation 1:13 a.m. CDT or 1:03 a.m. CST?)

Most of Canada’s time experts work in a place called Building M-36 (which involuntarily conjures up for me visions of the X-Files and Area 51.) They work in the Frequency and Time program in the Measurement Science and Standards portfolio with the National Research Council of Canada (NRC) on Montreal Road in Ottawa. Physicist Rob Douglas, the principal research officer, however, can be found on Saskatchewan Drive in Edmonton.

Douglas explained to me years ago that “in a handwritten log the hour of ambiguity to which you refer can be simply resolved by appending the time zone (e.g. CST or CDT) to potentially ambiguous entries … e.g. “01:32 CDT” for the first pass through the hour of ambiguity and “1:32 CST” during the second pass.

“By explicitly writing the time zone as part of the time entry,” Douglas added, “you also bypass the time acts’ defaults for official time – as you might wish to do if you are making agreements across a time zone boundary where there is the possibility of geographic ambiguity of time zone.

“The above procedure is very clear in Canada, but unfortunately less so in the USA,” said Douglas. “We in Canada can refer to ‘official’ or ‘legal’ time, which can alternate between being a ‘Standard Time’ or being a ‘Daylight Time.’ In the USA, to allow regulation by the federal government, both ‘Standard Time’ and ‘Daylight Time’ must be considered a ‘standard’ to avoid having time changes be a state responsibility under the residual powers clause of their constitution. If you think you may have to deal with the American ambiguity, it may be worthwhile to include an explanatory note in the log, such as ‘CST is defined as UTC-6h, and CDT is defined as UTC-5h.’

“If the times are being logged in a permanent logbook, with entries in chronological order for a fixed reckoning of time (i.e. in the absence of clock adjustments), then a simple way of removing the ambiguity is to include in the appropriate place in the log an entry such as “02:00 CDT – log’s clock changed from CDT to CST – 01:00 CST.

“If the log is a computer log, by using the operating system’s timestamps (for example as the time recorded for a file’s modification) the problem disappears since these timestamps are recorded as Coordinated Universal Time (UTC – the modern version of Greenwich Mean Time) which is never subjected to Standard/Daylight changes. The operating system re-interprets these timestamps into its version of the correct local time in effect for the particular UTC timestamp, and this re-interpretation may unfortunately still be expressed ambiguously, but the underlying UTC timestamp can be used to resolve any ambiguity about time zones and Daylight/Standard time.”

You can also follow me on X (formerly Twitter) at: https://twitter.com/jwbarker22